|

~SOLD~CHESHIRE Leonard Geoffrey

CHESHIRE Leonard Geoffrey

Group Captain Geoffrey Leonard Cheshire, Baron Cheshire, VC, OM, DSO and Two Bars, DFC (7 September 1917 – 31 July 1992)

After learning basic piloting skills with the Oxford University Air Squadron, after the outbreak of the Second World War, Cheshire joined the RAF as a Pilot Officer. He was initially posted in June 1940 to 102 Squadron, flying Armstrong Whitworth Whitley medium bombers, from RAF Driffield. In November 1940, Cheshire was awarded the DSO for flying his badly damaged bomber back to base.

In January 1941, Cheshire completed his tour of operations, but then volunteered immediately for a second tour. He was posted to 35 Squadron with the brand new Handley Page Halifax and completed his second tour early in 1942, by then, a Squadron Leader. August 1942 saw a return to operations as CO of No. 76 Squadron RAF. The squadron had recently suffered high losses operating the Halifax, and Cheshire immediately tackled the low morale of the unit by ordering an improvement in the performance of the squadron aircraft by removing the mid-upper and nose gun turrets along with exhaust covers and other weighty non-essential equipment. This allowed the bombers to fly higher and faster. Losses soon fell and morale rose accordingly. Cheshire was amongst the first to note there was very low return rate of Halifax bombers on three engines; furthermore, there were reports the Halifax was unstable in a “corkscrew” which was the manoeuvre used by bomber pilots to escape night fighters. The test pilot Eric Brown DSC and (just) a flight engineer undertook risky tests to establish the cause and were told a representative of Bomber Command would fly with them. Brown remembers “We couldn`t believe it, it was Cheshire! We were astonished to say the least. I asked him not to touch (the controls) and to his ever lasting credit he never commented at all, he just sat in the second pilot`s seat and raised his eye brows at what we were doing !” The fault was in the Halfax`s rudder design and Cheshire became enraged when Handley Page at first declined to make modifications so as not to disrupt production.

During his time as the Commanding Officer of 76 Squadron at RAF Linton, Cheshire took the trouble to recognise and learn the name of every single man on the base. He was determined to increase the efficiency of his squadron and improve the chances of survival of its crews, to this end he constantly lectured crews on the skills needed to achieve those aims. The crews knew he was devoted to their interests and when, on an operation to Nuremberg, they were told to cross the French Coast at 2,000 ft (the most dangerous height for light flak). Cheshire simply refused, stating they would fly at 200 ft or 20,000 ft. Typically, Cheshire inspired such loyalty and respect that the ground crews of 76 Squadron were proud to chorus “We are Cheshire cats!”.

In 1943, Cheshire published an account of his first tour of operations in his book, Bomber Pilot which tells of his posting to RAF Driffield and the story of flying his badly damaged bomber ("N for Nuts") back to base. In the book, Cheshire fails to mention being awarded the DSO for this, but does describe the bravery of a badly burnt member of his crew.

No. 617 SquadronCheshire became Station Commander RAF Marston Moor in March 1943, as the youngest Group Captain in the RAF, although the job was never to his liking and he pushed for a return to an operational command. These efforts paid off with a posting as commander of the legendary 617 "Dambusters" Squadron in September 1943. While with 617, Cheshire helped pioneer a new method of marking enemy targets for Bomber Command's 5 Group, flying in at a very low level in the face of strong defences, using first, the versatile de Havilland Mosquito, then a North American P-51 Mustang fighter.

On the morning before a planned raid by 617 squadron to Siracourt, a crated P-51 Mustang turned up at Woodhall Spa, it was a gift for Cheshire from his admirers in the U.S. 8th Air Force. Cheshire had the aircraft assembled and the engine tested as he was determined to test the possibilities of the fighter as a marker aircraft. He took off, in what was his first flight in the aircraft, and caught up with 617`s Lancasters before they reached the target. Cheshire then proceeded to accurately mark the target (a V-1 storage depot) for the heavies which landed three Tallboys on it. He then flew back and landed the P-51 in the dark.

This development work in target marking was the subject of some severe intraservice politics; Cheshire was encouraged by his 5 Group Commander Air Vice-Marshal Ralph Cochrane, although the 8 Group Pathfinder AOC Air Vice-Marshal Don Bennett saw this work as impinging on the responsibilities of his own command.

Victoria Cross

Cheshire was nearing the end of his fourth tour of duty in July 1944, having completed a total of 102 missions, when he was awarded the Victoria Cross. He was the only one of the 32 VC airmen to win the medal for an extended period of sustained courage and outstanding effort, rather than a single act of valour. His citation noted:

In four years of fighting against the bitterest opposition he maintained a standard of outstanding personal achievement, his successful operations being the result of careful planning, brilliant execution and supreme contempt for danger – for example, on one occasion he flew his P-51 Mustang in slow 'figures of eight' above a target obscured by low cloud, to act as a bomb-aiming mark for his squadron. Cheshire displayed the courage and determination of an exceptional leader.

It also noted a raid in which he had marked a target, flying a Mosquito at low level against "withering fire".

When Cheshire went to Buckingham Palace to receive his VC from King George VI, he was accompanied by Norman Jackson who was also due to receive his award on that day. Cheshire insisted that despite the difference in rank (Group Captain and Warrant Officer), they should approach the King together. Jackson remembers that Cheshire said to the King, "This chap stuck his neck out more than I did - he should get his VC first!" The King had to keep to protocol, but Jackson commented he would "never forget what Cheshire said."

Later operations

A portrait of Chesire in 1945One of Cheshire's missions was to use new 5,400 kilograms (12,000 lb) "Tallboy" deep-penetration bombs to destroy V3 long-range cannons located in underground bunkers near Mimoyecques in the Pas-de-Calais region of northern France. These were powerful guns able to fire a 500 lb shell into London every minute. They were protected by a concrete layer. The raid was planned so the bombs hit the ground next to the concrete to destroy the guns from underneath. Although considered successful at the time, later evaluations confirmed that the raids were largely ineffectual.

Cheshire was, in his day, both the youngest Group Captain in the service and, following his VC, the most decorated. In his book, Bomber Command (2010), Sir Max Hastings states “Cheshire was a legend in Bomber Command, a remarkable man with an almost mystical air about him, as if he somehow inhabited a different planet from those about him, but without affectation or pretension”. Cheshire would always fly on the most dangerous operations, he never took the easy option of just flying on the less risky ops to France, a habit which caused some COs to be referred to derisively as "François" by their men. Cheshire had no crew but would fly as “Second Dickey”, with the new and nervous to give them confidence.

Cheshire had strong feelings on any crew displaying LMF (Lack of Moral Fibre, a euphemism for cowardice) when subject to the combat stress of Bomber Command`s sorties (many of which had loss rates of 5% or more). Even as a brilliant and sympathetic leader, he wrote “I was ruthless with LMF, I had to be. We were airmen not psychiatrists. Of course we had concern for any individual whose internal tensions meant that he could no longer go on but there was a worry that one really frightened man could affect others around him. There was no time to be as compassionate as I would like to have been.” Thus Cheshire transferred LMF cases out of his squadron almost instantaneously (like every other RAF squadron did at the time). This was also because he argued that a man who thought he was doomed would collapse or bail out when his aircraft was hit, whereas Cheshire thought if he could survive the initial shock of finding his aircraft damaged, he had more of a chance of survival.

On his 103rd mission, Cheshire was the official British observer of the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki. His vantage point was in the support B-29 Big Stink. He did not witness the event as close up as anticipated due to aircraft commander James Hopkins' failure to link up with the other B-29s. Hopkins was meant to join with the others over Yakushima, but he circled at 39,000 ft instead of the agreed height of 30,000 ft. He tried to justify this by the need to keep the VIP passengers out of danger, but Cheshire thought that Hopkins was "overwrought".

"Many assumed that it was Nagasaki which emptied him; as Cheshire kept pointing out, however, it was the war as a whole. Like Britain herself, he had been fighting or training for fighting since 1939." He was earlier quoted as saying: "... then I for one hold little brief for the future of civilization".

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

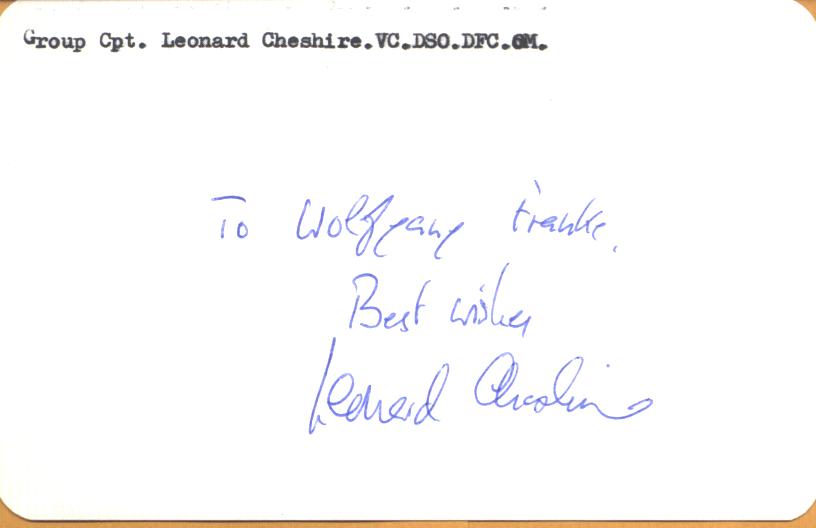

Signed index card

Price: $0.00

Please contact us before ordering to confirm availability and shipping costs.

Buy now with your credit card

other ways to buy

|