|

JOHNSON, Johnnie / CUNNINGHAM John

Johnnie Johnson

Air Vice Marshal James Edgar "Johnnie" Johnson CB, CBE, DSO & Two Bars, DFC & Bar (9 March 1915 – 30 January 2001) was a Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot and flying ace—defined as a pilot that has shot down five or more enemy aircraft in aerial combat—who flew and fought during the Second World War and Korean War.

Born in 1915, Johnson grew up and was educated in the East Midlands, where he qualified as an engineer. A sportsman and hunter, Johnson attributed his fighter skills to his experiences shooting wildfowl with a shotgun. While playing rugby he broke his collarbone; an injury that later complicated his ambitions of becoming a fighter pilot. Johnson had been interested in aviation since his youth, and applied to join the RAF; initially rejected, first on social, and then on medical grounds, in August 1939 he was eventually accepted. The injury problems, however, returned during his early training and flying career, resulting in him missing the campaigns in the Low Countries and France and the Battle of Britain. In 1940 Johnson had an operation to reset his collarbone, and began flying regularly. He took part in the offensive sweeps over occupied Europe from 1941 to 1944, almost without rest. Johnson was involved in heavy aerial fighting during this period. His combat tour included participation in the Dieppe Raid, Combined Bomber Offensive, Battle of Normandy, Operation Market Garden and the Battle of the Bulge and the Western Allied invasion of Germany.

Johnson was credited with 34 individual victories over enemy aircraft, as well as seven shared victories, three shared probables, 10 damaged, three shared damaged and one destroyed on the ground. Johnson flew 700 operational sorties and engaged enemy aircraft on 57 occasions. Included in his list of individual victories were 14 Messerschmitt Bf 109s and 20 Focke-Wulf Fw 190s destroyed making him the most successful RAF ace against the Fw 190. This score made him the highest scoring Western Allied fighter ace against the German Luftwaffe.

Johnson continued his career in the RAF after the war, and served in the Korean War, retiring in 1966, with the rank of air vice marshal. He maintained an interest in aviation and did public speaking on the subject as well as entering into the business of aviation art. Johnnie Johnson remained active until his death from cancer in 2001.

Early life

Johnson was born 9 March 1915 in Barrow upon Soar, Leicestershire, to Alfred Johnson and Beatrice May Johnson. He lived and was brought up in Melton Mowbray, where his father was a policeman, and educated at Camden Street Junior School and Loughborough Grammar School. Johnson's uncle, Edgar Charles Rossell, who had won the Military Cross with the Royal Fusiliers in 1916, paid for Johnson's education at Loughborough. According to his brother Ross, during his time there, Johnson was nearly expelled after refusing punishment for a misdemeanour, believing it to be unjustified: "he was very principled and simply dug his heels in". Among Johnson's hobbies and interests was shooting and sports; he shot rabbits and birds in the local countryside. Johnson attributed his fighter skills to his experiences shooting wildfowl with a shotgun.

Johnson attended the University of Nottingham, where he qualified as a civil engineer, aged 22. Johnson became a surveyor at Melton Mowbray Urban District Council before progressing to assistant engineer with Chigwell Urban District Council at Loughton. In 1938, Johnson broke his collarbone playing rugby for Chingford Rugby Club; the injury was wrongly set and did not heal properly, which later caused him difficulty at the start of his flying career.

Joining the RAF

Keen to follow up his interest in aviation, Johnson started taking flying lessons at his own expense. He applied to join the Auxiliary Air Force (AAF) but encountered some of the social problems that were rife in British society at the time. Johnson strongly felt he was rejected on the grounds of his class status. Johnson's fortunes were to improve. As the chances of war increased in the aftermath of the Munich Crisis, the standards of the RAF were relaxed, however, as the service expanded and brought in men from ordinary social backgrounds. Johnson re-applied to the AAF. He was informed that sufficient pilots were already available but there were some vacancies in the balloon squadrons. Johnson rejected the offer.

Inspired by some Chingford friends that had joined, Johnson applied again to join the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR). He was rejected on the grounds that there were too many applicants for vacancies and his injury made him unsuitable for flight operations. He then joined the Leicestershire Yeomanry, where the injury was not a bar to recruitment. He joined the Territorial Army unit because, though he was in a reserved occupation, if war came, he had "no intention of seeing out the duration building air raid shelters or supervising decontamination squads".

Flight training

In August 1939, Johnson was accepted by the RAFVR. Taught by retired service pilots of 21 Elementary & Reserve Flying Training School, Johnson trained on the de Havilland Tiger Moth biplane. Upon the outbreak of war in September 1939, with the rank of sergeant, Johnson entrained for Cambridge. He arrived at the 2nd Initial Training Wing to begin flight instruction. He was interviewed by senior officers in which he said his profession would make him more useful in a reconnaissance role. The wing commander agreed, but nonetheless, Johnson was selected for fighter pilot training.

By December 1939, Johnson began his initial training at 22 EFTS (Elementary Flying Training School), Cambridge. He flew only three times in December 1939 and eight in January 1940, all as second pilot. On 29 February 1940, Johnson flew solo for the first time in Tiger Moth N6635. On 15 March and 24 April, his passed a 50-minute flight test. The chief flying instructor passed him on 6 May. He then moved to 5 FTS at Sealand before completing training at 7 OTU (Operational Training Unit) – RAF Hawarden in Wales flying the Miles Master N7454 where he earned his instrument, navigation, night-flying ratings and practised forced landings. After training was complete on 7 August 1940, Johnson received his "wings" and was immediately inducted into the General Duties Branch of the RAF as a pilot officer with 55 hours and 5 minutes solo flying.

0n 19 August 1940, Johnson flew a Spitfire for the first time. Over the next weeks he practised handling, formation flying, attacks, battle climbs, aerobatics and dogfighting. During his training flights, he stalled and crashed a Spitfire. Johnson had his harness straps on too loose, and wrenched his shoulders – revealing that his earlier rugby injury had not healed properly. The Spitfire did a ground loop, ripping off one of the undercarriage legs and forcing the other up through the port mainplane. The commanding officer excused Johnson, for the "short airfield" was difficult to land on for an inexperienced pilot. Johnson got the impression, however, that he would be watched closely, and felt that if he made another mistake, he would be "certainly washed out". Johnson tried to pack the injured shoulder with wool, held in place by adhesive tape. He also tightened the straps to reduce vibrations. Johnson found he had lost his "feel" in his right hand, and it became numb. When he practised dives, the pressure also aggravated his shoulder. He often tried to fly using his left hand only, but the Spitfire would have to be handled with both hands during anything other than simple manoeuvres. Despite the difficulties with his injuries, on 28 August 1940, the course was complete. Johnson had 205.25 hours on operational types including 23.50 on the Spitfire.

Injury resurfaces

After training, in August 1940, he was briefly posted to No. 19 Squadron as a probationary pilot officer. Due to equipment difficulties, 19 Squadron were unable to complete Johnson's training and he left the unit.

On 6 September 1940 Johnson was posted to 616 Squadron at RAF Coltishall. Squadron Leader H.L "Billy" Burton took Johnson on a 50-minute training flight in X4055. After the flight Burton impressed upon Johnson the difficulties of deflection shooting and the technique of a killing shot from line-astern or near line-astern positions; the duty of the number two whose job was not to shoot down enemy aircraft but to ensure the leader's tail was safe. Burton also directed Johnson to some critical tactical essentials; the importance of keeping good battle formation and the tactical use of sun, cloud and height. Five days later, Johnson flew an X-Raid patrol in Spitfire X4330, qualifying for the Battle of Britain clasp.

Johnson's old injury continued to trouble him and he found flying high performance aircraft like the Spitfire extremely painful. RAF medics gave him two options; he could have an operation that would correct the problem, but this meant he would miss the Battle of Britain, or becoming a training instructor flying the light Tiger Moth. Johnson opted for the operation. He had hoped for discreet treatment, but word soon reached the CO, and Johnson was taken off flying duties and sent to the RAF Hospital at Rauceby. He did not return to the squadron until 28 December 1940. CO Burton took Johnson up for a test flight on 31 December 1940 in Miles Magister L8151. After the 45-minute flight, Johnson's fitness to fly was approved.

Second World War

616 Squadron

Johnson returned to operational flying in early 1941 in 616 Squadron, which was forming part of the Tangmere Wing. Johnson often found himself flying alongside Wing Commander Douglas Bader and Australian ace Tony Gaze DFC**. On 15 January 1941, Johnson, the recently appointed Squadron Leader Burton and Pilot Officer Hugh Dundas, who arrived back at the squadron on 13 September 1940, took off to offer cover for a convoy off North Coates. The controller vectored the pair onto an enemy aircraft, a Dornier Do 17. Both attacked the bomber and lost sight of it and each other. Although the controllers intercepted distress signals from the bomber Johnson did not see it crash. They were credited with one enemy aircraft damaged. It was the only time Johnson was to engage a German bomber. By the end of January, Johnson had added another 16.35 flying hours on Spitfires.

In the opening months, Johnson flew as a night fighter pilot. Using day fighters to act as night fighters without radar was largely unsuccessful in intercepting German bombers during The Blitz; Johnson's only action occurred on 22 February 1941 when he damaged a Messerschmitt Bf 110 in Spitfire R6611, QJ-F. A week later, Johnson's squadron was moved to RAF Tangmere on the Channel coast. Johnson was eager to see combat after just 10.40 operational hours and welcomed the prospect of meeting the enemy from Tangmere. If the Germans did not resume their assault the Wing was to take the fight to them.

Johnson's first contact with enemy fighters did not go as planned. Bader undertook a patrol with Dundas as his number two. Johnson followed in his section as number three with "Nip" Nepple guarding his tail as Red Four. Johnson spotted three Bf 109s a few hundred feet higher and travelling in the same direction. Johnson, forgetting to calmly report the number, type and position of the enemy, shouted, "Look out Dogsbody!" (Bader's call sign). Such a call was only to be used if the pilot in question was in imminent danger of being "bounced". The Section broke in all directions and headed to Tangmere singly. The mistake brought an embarrassing rebuke from Bader at the debriefing.

Johnson flew various operations over France including the 'Rhubarb' ground attack missions which Johnson hated—he considered it a waste of pilots. Several aces, including Paddy Finucane and Eric Lock were killed and Robert Stanford Tuck would be captured carrying out these sweeps. During this time, Dundas and other pilots expressed dissatisfaction with the formation tactics being used. After a long conversation into the early hours, Bader accepted the suggestions by his senior pilots and agreed to the use of more flexible tactics to lessen the chances of being taken by surprise, or "bounced". The tactical changes involved operating overlapping line abreast formations similar to the German Finger-four formation. The tactics were used thereafter by RAF pilots in the Wing.

The first use of these tactics by the Tangmere Wing was used on 6 May 1941. The Wing engaged Bf 109Fs from Jagdgeschwader 51 (Fighter Wing 51), led by Werner Mölders. Noticing the approaching Germans below and behind them, the Spitfires feigned ignorance. Waiting for the optimum moment to turn the tables, Bader called for them to break, and whip around behind the Bf 109s. Unfortunately, while the tactic had been successful in avoiding a surprise attack, the break was mistimed. It left some Bf 109s still behind the Spitfires. In the battle that followed the Wing shot down one Bf 109 and damaged another, although Dundas was shot down for the second time in his career—and once again by Mölders, who had remained behind the British. Dundas was able to nurse his crippled fighter back to base and crash-land.

First aerial battles: becoming an ace

One month later, Johnson gained his first air victory. On 26 June Johnson participated in Circus 24. Crossing the coast near Gravelines, Bader warned of 24 Bf 109s nearby, southeast, in front of the Wing. The Bf 109s saw the British and turned to attack the lower No. 610 Squadron from the rear. While watching three Bf 109s above him dive to port, Johnson lost sight of his wing commander at 15,000 feet. Immediately a Bf 109E flew in front of him and turned slightly to port at a range of 150 yards. After receiving hits, the Bf 109's hood was jettisoned and the pilot baled out. Several No. 145 Squadron pilots witnessed the victory. He had expended 278 rounds from P7837's guns. The Bf 109 was one of five lost by Jagdgeschwader 2 (Fighter Wing 2) that day.

A flurry of action followed. On 1 July 1941 he expended 89 rounds and damaged Bf 109E. Bader's section was attacked and Johnson out-turned his assailant. Firing, he saw glycol streaming behind it. On 14 July, the Tangmere Wing flew on Circus 48 to St Omer. Losing sight of the squadron, Johnson and his wingman proceeded inland at 3,000 feet after spotting three aircraft. Turning in behind them, he identified them as Bf 109Fs. Johnson dived so as to come up and underneath into the enemy's blind spot. Closing to 15 yards, he gave the trailing Bf 109 a two-second burst. The tail was blown off and his windshield was covered in oil from the Messerschmitt. Johnson saw the other Bf 109s spinning down out of control. Having also lost his wingman, Johnson disengaged. Climbing and crossing the coast at Etaples, Johnson bounced a Bf 109E. Giving chase in a dive to 2,000 feet and firing at 150 yards, he observed something flying off the Bf 109's starboard wing. Johnson could not see any more owing to the oil-covered windscreen and did not make a claim. His second victory was probably Unteroffizier (Corporal) R. Klienike, III./Jagdgeschwader 26 (Third Group, Fighter Wing 26) who was posted missing.

On 21 July, Johnson shared in the destruction of another Bf 109 with Pilot Officer Hepple. Johnson's wingman disappeared during the battle. Sergeant Mabbet was mortally wounded but made a wheels-up landing near St Omer. Impressed with his skilful flying while badly wounded, the Germans buried him with full honours. On 23 July, Johnson damaged another Bf 109. During this battle Adolf Galland, Geschwaderkommodore (Wing Commander) of Jagdgeschwader 26 (Fighter Wing 26) was wounded; his life was saved by a recently installed armour plate behind his head.

Johnson took part in the 9 August 1941 mission in which Bader was lost over France. During the sortie, he destroyed a solitary Messerschmitt Bf 109. Johnson flew as wingman to Dundas in Bader's section. As the Wing crossed the coast, around 70 Bf 109s were reported in the area, the Luftwaffe aircraft outnumbering Bader's Wing by 3:1. Spotting a group of Bf 109s 1,000 feet below them, Bader led a bounce on a lower group. The formations fell apart and the air battle became a mass of twisting aircraft;

It seemed to me the biggest danger was a collision rather than being shot down, that's how close we all were. We got the 109s we were bouncing then (Squadron Leader) Holden came down with his section, so there were a lot of aeroplanes ... just 50 yards apart. It was awful ... all you could think about was surviving, getting out of that mass of aircraft.

Johnson exited the mass of aircraft and was immediately attacked by three Bf 109s. The closest was 100 yards away. Maintaining a steep, tight, spiralling turn, he dived into cloud and immediately headed for Dover. Coming out of the cloud, Johnson saw a lone Bf 109. Suspecting it to be one of the three that had chased him, he searched for the other two. Seeing nothing, Johnson attacked and shot it down. It was his fourth victory. Johnson ended his month's tally by adding a probable victory on 21 August. But it had been a bad day and month for the Wing. The much loathed Circus and Rhubarb raids had cost Fighter Command 108 fighters. The Germans lost just 18. On 4 September 1941 Johnson was promoted to flight lieutenant and awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC).

Johnson's last certain victories of the year were achieved on 21 September 1941. Escorting Bristol Blenheims to Gosnay, the top cover wings failed to rendezvous with the bombers. Near Le Touquet at 15:15 and around 20,000 feet, Johnson's section was bounded by 30 Bf 109s. Johnson broke and turned in and behind a Bf 109F. Approaching from a quarter astern and slightly below, Johnson fired closing from 200 to 70 yards. Pilot Officer Smith of Johnson's section observed the pilot bail out. Pursued by several enemy aircraft, Johnson dived to ground level. About 10 miles off Le Touquet, other Bf 109s attacked. Allowing the Germans to close within range, Johnson turned into a steep left-hand turn. It took him onto the tail of a Bf 109. Johnson fired and broke away at 50 yards. The Bf 109 was hit, stalled and crashed into the sea. Johnson was pursued until 10 miles south of Dover. The two victories made Johnson's total to six destroyed, which now meant he was an official flying ace. In winter 1941, Johnson and 616 Squadron moved to training duties. The odd convoy patrol was flown but it was an idle period for the Squadron which had now concluded its "Tangmere tour".

Squadron Leader No. 610 Squadron

On 31 January 1942, the Squadron moved to RAF Kings Cliffe. After an uneventful few months, RAF Fighter Command resumed its offensive policy in April 1942 when the weather cleared for large-scale operations. Johnnie flew seven sweeps that month. But the situation had now changed. The Spitfire V, which was flown by the RAF had been a match for the Bf 109F, however, the Germans had introduced an new fighter: the Focke-Wulf Fw 190. It was faster at all altitudes below 25,000 feet, possessed a faster roll rate, was more heavily armed and could out-dive and out-climb the Spitfire. Only in the turn could the Spitfire outperform the Fw 190. The introduction of this new enemy fighter resulted in heavier casualty rates among the Spitfire squadrons until a new mark of Spitfire could be produced. Johnson claimed a damaged Fw 190 on 15 April 1942 but he witnessed the Fw 190s get the better of the British pilots consistently throughout most of 1942:

Yes, the 190 was causing us real problems at this time. We could out-turn it, but you couldn't turn all day. As the number of 190s increased, so the depth of our penetrations deceased. They drove us back to the coast really.

On 25 May, Johnson experienced an unusual mission. His section engaged a Dornier Do 217 carrying British markings, four miles west of his base. Johnson allowed the three inexperienced pilots to attack it, but they only managed to damage the bomber. Days later, on 26 June 1942, Johnson was awarded the bar to his DFC. More welcome news was received late in the month as the first Spitfire Mk. IXs began reaching RAF units. On 10 July 1942, Johnson was promoted to the rank of squadron leader, effective as of the 13 July, and given command of 610 Squadron.

In "rhubarb" operations over France, Johnson's wing commander, Patrick Jameson, insisted that the line-astern formation be used which caused Johnson to question why tactics such as the finger-four had not been universally adopted. Johnson criticised the lack of tactical consistency and when his squadron flew top cover, he often changed to the finger-four as soon as they reached the French coast, hoping his wing leader wouldn't notice.

By August 1942, preparations were begun for a major operation, Jubilee, at Dieppe. The Dieppe raid took place on 19 August 1942. Johnson took off at 07:40 in Spitfire VB. EP254, DW-B. Running into around 50 Bf 109s and Fw 190s in fours, pairs and singly. In a climbing attack Johnson shot down one Fw 190 which crashed into the sea and shared in the destruction of a Bf 109F. While heading back to base, Johnson attacked an alert Fw 190 which met his attack head on. The dogfight descended from 8,000 to zero feet. Flying over Dieppe, Johnson dived towards a destroyer in the hope its fire would drive off the Fw 190, now on his tail. The move worked and Johnson landed back at RAF West Malling at 09:20. For the remainder of the year, the squadron was moved to RAF Castletown in September 1942 to protect the Royal Navy fleet at Scapa Flow.

Wing commander and the Canadians

Johnson took command of No. 144 Wing (Canadians) based at RAF Kenley after Christmas and they received the new Spitfire IX: the answer to the Fw 190. After gaining a probable against a Fw 190 in February 1943, Johnnie selected Spitfire EN398 after a 50-minute test flight on 22 March 1943. It became his regular mount. Being a wing commander now meant his initials could be painted on the machine. His Spitfires now carried JE-J. He was also allotted the call sign "Greycap".

Johnson set about changing the wing's tactical approach. He quickly forced the wing to abandon the line-astern tactics for the finger-four formation which offered much more safety in combat; enabling multiple pilots to participate in scanning the skies for enemy aircraft so as to avoid an attack, and also being better able to spot and position their unit for a surprise attack upon the enemy. Johnson made another alteration to his units operations. He loathed ground-attack missions which highly trained fighter pilots were forced to participate in. He abandoned ground attack missions whenever he could. During these weeks, Johnson's wing escorted United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) bombers to targets in France. On a fighter sweep, Ramrod 49, Johnson destroyed an Fw 190 for his eighth victory. Unteroffizier Hans Hiess from 6 Staffel bailed out, but his parachute failed to open. The spring proved to be a busy one; Johnson claimed three Fw 190s damaged two days later. On the 11 and 13 May he destroyed an Fw 190 to reach 10 individual air victories while sharing in the destruction of another on the later date and a Bf 109 on 1 June. A further five victories against Fw 190s were achieved in June; two on the 15th, one on the 17th (Unteroffizier Gunther Freitag, 8./JG 26 was killed), one destroyed and one damaged on 24th, and another victory on the 27th to bring his total to 15.

More success was had in July. The USAAF began Blitz Week; a concentrated effort against German targets. Escorting American bombers, Johnson destroyed three Bf 109s and damaged another, the last being shot down on 30 July; his tally stood at 18. There was still no standard formation procedure in Fighter Command, and Johnson's use of the finger-four made the wing distinct in the air. It earned 144 Wing the nickname "Wolfpack". The name remained until 144 Wing was moved to an Advanced Landing Ground (ALG) at Lashenden and was renamed No. 127 Wing RCAF, part of the RAF Second Tactical Air Force under the command of No. 83 Group RAF.

The tactics proved successful in the Canadian Wing. Johnson scored his 19—21 victories on 23 and 26 August, whilst claiming yet another Fw 190 on 4 September 1943. Johnsons 19th victory was gained against Oberfeldwebel (First-Sergeant) Erich Borounik 10./JG 26, who was killed. Johnson's 21st victim, Oberfeldwebel Walter Grunlinger 10./JG 26, was also killed.

Normandy Front

In the lead up to the Battle of Normandy and the D-Day landings Johnson continued to score regularly. His 22—23rd victories were achieved on 25 April 1944 and Johnson became the highest scoring ace still on operations. These victories were followed by another Fw 190 on the 5 May (no. 24); III./JG 26 lost Feldwebel Horst Schwentick and Unteroffizier Manfred Talkenberg killed during the air battle. After the landings in France on 6 June 1944, Johnson added further to his tally, claiming another five aerial victories that month including two Bf 109s on 28 June. The mission in which Johnson recorded his 26th victory on 22 June was particularly eventful; four more Fw 190s fell to his wing. After bouncing a formation of Bf 109s and Fw 190s, he shot down a Bf 109 for his 29th victory. Five days later, Johnson destroyed two Fw 190s to reach his 30—31st air victories.

Johnson's wing was the first to be stationed on French soil following the invasion. With their radius of action now far extended compared to the squadrons still in Britain, the wing scored heavily through the summer. On 21 August 1944, Johnson was leading No. 443 Squadron on a patrol over the Seine, near Paris. Johnson bounced a formation of Focke-Wulf Fw 190s, shooting down two, which were recorded on the cine camera. Climbing back to his starting point at 8,000 ft, Johnson attempted to join a formation of six aircraft, he thought were Spitfires. The fighters were actually Messerschmitt Bf 109s. Johnson escaped by doing a series of steep climbs, during which he nearly stalled and blacked out. He eventually evaded the Messerschmitts, which had been trying to flank him on either side, while two more stuck to his tail. Johnson's Spitfire IX was hit by enemy aircraft fire for the only time, taking cannon shells in the rudder and elevators. Johnson had now equalled and surpassed Sailor Malan's record score of 32, shooting down two Fw 190s for his 32—33 air victories. However Johnson considered Malan's exploits to be better. Johnson points out, when Malan fought (during 1940—41), he did so outnumbered, and had matched the enemy even then. Johnson said:

Malan had fought with great distinction when the odds were against him. He matched his handful of Spitfires against greatly superior numbers of Luftwaffe fighters and bombers. He had been forced to fight a defensive battle over southern England and often at a tactical disadvantage, when the top-cover Messerschmitts [Bf 109s and Bf 110s] were high in the sun. I had always fought on the offensive, and, after 1941, I had either a squadron, a wing or sometimes two wings behind me.

Market Garden to VE Day

In September 1944 Johnson's wing participated in support actions for Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands. On 27 September 1944, Johnson's last victory of the war was over Nijmegen. His flight bounced a formation of nine Bf 109s, one of which Johnson shot down. During this combat Squadron leader Henry "Wally" MacLeod, of the Royal Canadian Air Force, and his squadron had joined Johnson. It was during this action that MacLeod went missing, possibly shot down by Siegfried Freytag of Jagdgeschwader 77.

The wing rarely saw enemy aircraft for the remainder of the year. Only on 1 January 1945 did the Germans appear in large numbers, during Operation Bodenplatte to support their faltering attack in the Ardennes. Johnson witnessed the German attack his wing's airfield at Brussels–Melsbroek. He recalled the Germans seemed inexperienced and their shooting was "atrocious". Johnson led a Spitfire patrol to prevent a second wave of German aircraft attacking but engaged no enemy aircraft, since there was no follow-up attack. From late January and through most of February, little flying took place.

In March 1945, Johnson patrolled as Operation Plunder and Operation Varsity pushed Allied armies into Germany. There was little sign of the Luftwaffe. Numerous ground-attack operations were carried out instead. On 26 March Johnson's wing was relocated to Twente and he was promoted to group captain. Days later Johnson took command of No. 125 Wing. On 5 April, after returning from patrol in Spitfire Mk XIV MV268, he switched off the engine just as a Bf 109 flew overhead. Seeing the Spitfire, it turned in for an attack; Johnson took cover under his fighter while the airfield defences shot down the 109. On 16 April 1945 Johnson's Wing moved to RAF Celle in Germany.

During the last week of the war, Johnson's squadron flew patrols over Berlin and Kiel as German resistance crumbled. During a flight over central Germany looking for jet fighters, Johnson's squadron attacked Luftwaffe airfields. On one sortie, his unit strafed and destroyed 11 Bf 109s that were preparing to take off. On another sortie, an enemy transport was sighted, but took evasive action and retreated back to German held territory but Johnson's pilots shot it down. On another occasion, Johnson intercepted a flight of four Fw 190s. The German fighters, however, waggled their wings to signal non-hostile intent and Johnson's unit escorted them to an RAF airfield.

After the German capitulation in May 1945, Johnson relocated with his unit to Copenhagen, Denmark. Here, his association with the Belgian No. 350 Squadron RAF led him to be awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm and the rank of Officer of the Order of Léopold with Palms.

Post-war

After the war Johnson commanded RAF Second Tactical Air Force at RAF Wildenrath in the West Germany from 1952 to 1955. In 1956 he wrote his wartime memoir, Wing Leader and in followed it up in 1964 with Full Circle, a history of air fighting, co-written with Percy "Laddie" Lucas, a former Member of Parliament and Douglas Bader's brother-in-law.

Korean War

Johnson was given a permanent commission by the RAF after the war (initially as a squadron leader, although retaining his wartime substantive rank as wing commander, and later confirmed in that rank), becoming OC Tactics at the Central Fighter Establishment. After an exchange posting to the USA, he flew North American F-86 Sabres with Tactical Air Command and went on to serve in the Korean War flying the Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star. Johnson did not leave any written record of his experiences in the Korean War. It is believed he saw action against enemy aircraft. For his service he received the Air Medal and Legion of Merit from the United States.

In 1951, Johnson commanded a wing at RAF Fassberg. The following year Johnson became air officer commanding (AOC) RAF Wildenrath from 1952 to 1954. From 1954 to 1957 he was deputy director, operations at the Air Ministry. On 20 October 1957, Johnson became AOC RAF Cottesmore in Rutland commanding V bombers. An air commodore by 1960, he attended the Imperial Staff College and served in No. 3 Group RAF commanding RAF Middle East at Aden. In June 1960, he was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). In 1965, Johnson was promoted air vice marshal and appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB). He retired in 1966.

Later life

Johnson was appointed a Deputy Lieutenant for the County of Leicestershire in 1967.[87] He established the Johnnie Johnson Housing Trust in 1969 and by 2001 the housing association managed over 4,000 properties. After the death of his friend Douglas Bader in 1982, Johnson, Denis Crowley-Milling and Sir Hugh Dundas set up the Douglas Bader Foundation, to continue supporting disabled charities, of which Bader was a passionate supporter.

Johnson was also the first to recognise the skills of Robert Taylor, aviation artist, in the 1980s. Depictions of aircraft and battle scenes in print began to become popular and he helped Taylor promote them. The venture was successful and Johnson's sons set up their own distribution networks in the United States and Britain.

Johnson spent most of the 1980s and 1990s as a keynote speaker, fundraiser and spending time on his hobbies; travelling, fishing, shooting and walking his dogs. Johnson appeared on the long–running British television show This Is Your Life on 8 May 1985, the 40th anniversary of VE Day. Among the programme's guests was German fighter ace Walter Matoni. British wartime propaganda had alleged Johnson had challenged Matoni to a personal duel; a version of events denied by Johnson. The two men arranged to meet after the war but were unable to do so until the TV programme. Among other guests was Hugh Dundas, "Nip" Nepple, who flew alongside Johnson on his first operation—in which he earned a rebuke from Bader—Crowley-Milling, Johnson's former Wing Commander Patrick Jameson and his uncle, Charlie Rossell who was over 100 years old at the time.

Personal life

As a teenager Johnson became fascinated by speed and joined the Melton Car Club with two boyhood friends. Johnson enjoyed the lifestyle of cars and "pacey women". Although he had many early interests, Johnson would later settle and add to his family. On 14 November 1942, Johnson married Pauline Ingate in Norwich during home leave. Hugh Dundas acted as best man and Lord Beaverbrook's son, Wing Commander Max Aitken also attended. During the war Pauline worked for the Fire Service. They had two sons: Michael (16 October 1944) and Chris (born 1 December 1946). During the war Pauline worked for the Fire Service. After the couple split up, Johnson lived with his partner Janet Partridge.

On 30 January 2001, Johnson, aged 85 years, died from cancer. A memorial service took place on 25 April 2001 at St Clement Danes and the hymns Jerusalem and I Vow to Thee, My Country were played. His children scattered his ashes on the Chatsworth estate in Derbyshire. The only memorial was a bench dedicated to him at his favourite fishing spot on the estate; the inscription reads "In Memory of a Fisherman".

List of air victories

Johnson's wartime record was 515 sorties flown, 34 aircraft claimed destroyed with a further seven shared destroyed (totalling 3.5 kills), three probable destroyed, 10 damaged, and one shared, destroyed on the ground. All his "kills" were fighters. As a Wing Leader, Johnson was able to use his initials "JE-J" in place of squadron code letters. He scored the bulk of his victories flying two Mk IXs: EN398/JEJ in which he shot down 12 aircraft and shared five plus six and one shared damaged, while commanding the Kenley Wing; MK392/JEJ, an L.F Mk. IX, 12 aircraft plus one shared, destroyed on the ground. His last victory of the war was scored in this aircraft. Johnson ended the war flying a Mk XIVE, MV268/JEJ. His post-war mount was MV257/JEJ; it was the last Spitfire to carry his initials.

The ability to verify British claims against the British' main opponents in 1941 and 1942, JG 26 and JG 2, is very limited. Only two of the 30 volumes of War Diaries produced by JG 26 survived the war. Historian Donald Caldwell has attempted to use what limited German material is available to compare losses and air victory claims but acknowledges the lack of sources leave the possibility for error.

A list of the 34 individual victories.

Victory No. Date Flying Kills Notes

15 Jan 1941 Spitfire IA K4477 Dornier Do 17 half-share damaged Near North Coates.

1. 26 June 1941 Spitfire IA K4477 Messerschmitt Bf 109 Near North Coates. RAF Fighter Command claimed nine; JG 2 lost five and two pilots killed.[104] Johnson witnessed the pilot bale out.[105]

4 July 1941 Spitfire IIA P7837 Messerschmitt Bf 109 damaged Gravelines

2. 6 July 1941 Spitfire IIA P7837 Messerschmitt Bf 109 South of Dunkirk. RAF Fighter Command claimed 11; JG 26 reported two Bf 109s damaged.[106][107]

3. 14 July 1941 Spitfire VB P8707 Messerschmitt Bf 109 Fauquembergues, Unteroffizier (Corporal) Robert Klienike, III./Jagdgeschwader 26 (JG 26—Fighter Wing 26), missing.[38] According to the War Diary of JG 26, Klienike was confirmed to have been killed.[108]

21 July 1941 Spitfire IIA P7837 Messerschmitt Bf 109 half-share "probable" Merville, Nord

23 July 1941 Spitfire IIA P7837 Messerschmitt Bf 109 damaged 10 miles inland from Boulogne

4. 9 August 1941 Spitfire VB W3334 Messerschmitt Bf 109 and a half-share Bf 109 destroyed Over Béthune. RAF Fighter Command claimed 18; JG 26 lost two fighters.[109]

21 August 1941 Spitfire VB W3457 Messerschmitt Bf 109 "probable" 10 miles east Le Touquet.

4 September 1941 Spitfire VB W3432 Messerschmitt Bf 109 half-share "probable" 5miles off Le Touquet

5–6. 21 September 1941 Spitfire VB W3428 Two Messerschmitt Bf 109s Near Le Touquet

15 April 1942 Spitfire VB BM121 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 damaged 10 miles off Le Touquet

7. 19 August 1942 Spitfire VB EP215 "DW-B" Focke-Wulf Fw 190 and Fw 190 a half-share damaged, and third-share Bf 109F destroyed. Dieppe. Claimed during patrol from 07:40 – 09:10, it is likely his opponents were from I./JG 26 which landed at 09:30.[110] Of the six pilot losses JG 26 suffered, times are unknown for three. In the Dieppe area Oberfeldwebel Werner Gerhardt 5 staffel was killed in Fw 190A-3 Wrk. Nr. 538, code BK+3. Unteroffizier Heinrich von Berg was also killed in Fw 190A-3/U3 Wrk. Nr. 2240. The third pilot flew a Bf 109.[111] The third share Bf 109 destroyed was with P/O Smith and F/S Creagh.

20 August 1942 Spitfire VB EP215 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 "probable". Off French Coast

13 February 1943 Spitfire IX EP121 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 "probable". SW Boulogne

8. 3 April 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Montreuil, Pas-de-Calais, Unteroffizier Hans Hiess, 6./JG 26 (6 Staffel or Squadron) killed.[112]

5 April 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Three Focke-Wulf Fw 190 damaged Ostend-Ghent area

9. 11 May 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Gravelines.

10. 13 May 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 and a third-shared FW 190 destroyed. Berck-Le Touquet. Fighter Command claimed 10; I./JG 27 lost 2, III./JG 54 lost 1, JG 2 lost 4, JG 26 lost 2.

11. 14 May 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Near Nieuport.

1 June 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Half-share Messerschmitt Bf 109 destroyed Somme estuary. Three claimed by Wing; I/JG 27 lost three.

12–13. 15 June 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Two Focke-Wulf Fw 190s Yvetot. The Kenley Wing claimed 3; I./JG 2 lost two Fw 190s.[113]

14. 17 June 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Ypres-Saint-Omer, Unteroffizier Gunther Freitag, 8./JG 26. Crashed and killed at Steenvorde, Ypres, Flanders.[114]

15. 24 June 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 and one Fw 190 damaged Fécamp-Valmont, Seine-Maritime, Victim probably from Jafu 3's I./Jagdgeschwader 2 (JG 2—Fighter Wing 2).

16. 27 June 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 St Omer. According to the JG 26 War Diary the Germans claimed no victories and claimed to have sustained no losses.[115]

17. 15 July 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Messerschmitt Bf 109 Senarpont. Possibly versus I./JG 27.

18. 25 July 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Messerschmitt Bf 109 Schipol, Victim probably from III./Jagdgeschwader 54 (JG 54—Fighter Wing 54). The pilot was killed but the victim's identity is unknown. May possibly be either Unteroffizier Pfeiffe (baled out wounded), or Unteroffizier Werner Walther (killed).[116]

29 July 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Messerschmitt Bf 109 damaged SW Amsterdam

30 July 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Half-share Messerschmitt Bf 109 destroyed Schipol

12 August 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Half-share Messerschmitt Bf 109 destroyed and a half-share Bf 109 damaged. Axel area. Versus 11 'staffel JG 26. The War Diary records no losses.[117]

17 August 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Quarter-share Messerschmitt Bf 110 destroyed N. Ghent. Probably of ZG 26.

19. 23 August 1943 Spitfire IX EN398 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Gosnay, Oberfeldwebel (First-Sergeant) Erich Borounik 10./JG 26 Killed in Fw 190A-5 "Black 12". The victory was recorded on Johnson's gun camera film.[58]

20. 26 August 1943 Spitfire IX MA573 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Rouen, JG 26 War Diary has no entry for this date.[118]

21. 4 September 1943 Spitfire IX MA573 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Roubaix, Oberfeldwebel Walter Grunlinger 10./JG 26 killed.[59]

5 September 1943 Spitfire IX EN938 Messerschmitt Bf 109 damaged Daynze area.

22–23. 25 April 1944 Spitfire IXB MK392 Two Focke-Wulf Fw 190s Laon, Two victories witnessed by Pilot Officer Gomez and Flying Officer Stephens. Both saw the Fw 190s crash.[119]

28 March 1944 Spitfire IXB MK392 Half-share Junkers Ju 88 destroyed on ground. Dreux Airfield

24. 5 May 1944 Spitfire IXB MK392 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Douai, Among Johnson's opponents were III./JG 26. Feldwebel Horst Schwentick and Unteroffizier Manfred Talkenberg were both killed. Henry Wallace McLeod filed a claim and recorded the wreckage on his gun camera film over a field three miles east of Douai. Two more claims were made by Pilot Officer F.A.W.J. Wilson of 441 Squadron and Pilot Officer T.C. Gamey of the same unit. German records only record two losses. Johnson stated in his report that the Fw 190 pilot he shot down baled out.[60]

25. 16 June 1944 Spitfire IXB MK392 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Villers-Bocage, Somme, victory was recorded on gun camera film over an unidentified Fw 190.[120]

26. 22 June 1944 Spitfire IXB MK392 Messerschmitt Bf 109 7m W Argentan, victory recorded on gun camera film over an unidentified Bf 109. 144 Wing claimed four destroyed. Opponents were from III./JG 26 and JG 2.[121]

27–28. 28 June 1944 Spitfire IXB MK392 Two Messerschmitt Bf 109s Two victories over Caen; recorded on gun camera film over two unidentified Bf 109s.[122] 5. Jagd Division made a large effort in this area in support of German land defences during Operation Epsom. Around 24 Fw 190s and Bf 109s were lost – the Canadian Wing claimed 25 destroyed outright and a further one probable and 13 damaged. The Germans claimed five Spitfires and three American fighters. The action was so intense it is impossible to match up individual combats. III./JG 26 were equipped with Bf 109s and three Bf 109s were shot down, including Josef Menze who was injured. The other two pilots bailed out unhurt.[123] Helmut Schwartz-Arnyasy from Stab./JG 27, flying Bf 109G-6 Wrk Nr 163246 was shot down and posted missing in action north west of Caen.

29. 30 June 1944 Spitfire IXB NH380 Messerschmitt Bf 109.[62]

E Gace.

30–31. 5 July 1944 Spitfire IXB NH380 Two Focke-Wulf Fw 190s. Alençon. 144 Wing claimed four downed. Johnson's victims likely belonged to I./Jagdgeschwader 11 (Fighter Wing 11).[63] Oberleutnant Heinz-Gerhard Vogt, a 28-victory ace was shot down in this area in this battle. Vogt, of 7./JG 26, survived.[124]

20 July 1944 Spitfire IXB MK392 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 damaged. S Argentan

32–33. 23 August 1944 Spitfire IXB NH382 Two Focke-Wulf Fw 190s. Senlis. 127 Wing claimed 12 destroyed ( 8 Fw 190s, 4 Bf 109s) for three losses.[125]

34. 27 September 1944 Spitfire IXB NH382 Messerschmitt Bf 109 Rees on Rhine, probably belonging to Jagdgeschwader 77 (JG 77—Fighter Wing 77). Henry McLeod lost in combat with Siegfried Freytag.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

John Cunningham

Group Captain John "Cat's Eyes" Cunningham CBE DSO** DFC* (27 July 1917 – 21 July 2002), was a British Royal Air Force night fighter ace during World War II and a test pilot, both before and after the war. He was credited with 20 kills, of which 19 were claimed at night.

Early life

Cunningham was born in Croydon in South London, the son of the company secretary of the Dunlop Rubber Company. He first flew at a young age, while attending preparatory school at Sleaford. He was subsequently a pupil at Whitgift School, a public school in Croydon. After leaving school, he joined de Havilland Aircraft in 1935 as an apprentice. In the same year he also joined Royal Auxiliary Air Force and became a member of No. 604 (County of Middlesex) Squadron; he made his first solo flight in 1936.

Cunningham subsequently became a junior test pilot with de Havilland, working with light aircraft alongside Geoffrey de Havilland, the company founder's son.

World War 2

At the outbreak of World War II, Cunningham joined the Royal Air Force. Flying first Blenheims and then the powerful Bristol Beaufighter with No. 604 Squadron RAF.

Cunningham's first "kill" came on 19 November 1940 when, over the coast of Sussex, he shot down a Junkers Ju 88. He then downed two Heinkel 111 bombers and was awarded the DFC with bar.

By the end of the Blitz in May 1941 he had become the most famous night fighter pilot, successfully claiming 14 night raiders using airborne interception – the aircraft version of what later became known as radar. Most of his victories were achieved with Squadron Leader Jimmy Rawnsley as his radar operator, who later wrote the book Night Fighter detailing their exploits.

On 8 April 1942 he destroyed two bombers during the same sortie and a week later claimed three more kills which earned his first DSO.

Following the downing of his sixteenth kill in July 1942, Cunningham received the second bar award to the DSO. Whilst a Wing Commander with No. 85 Squadron RAF flying a Mosquito he claimed his twentieth and last wartime kill which earned him his third DSO in March 1944.

Cunningham's nickname of Cat's Eyes came from British propaganda explanations to cover up the use of airborne interception. It was claimed a special group of British pilots ate carrots for many years to develop superior night vision. Cunningham himself, a self-effacing and modest individual, detested this nickname.

Later serving as Commanding Officer of No. 85 Squadron RAF in 1943–44 flying Mosquitoes, Cunningham survived the war as a Group Captain with 20 claims.

Postwar

Cunningham returned to de Havilland as a test pilot after the war. In 1946, he succeeded Geoffrey de Havilland Jr as chief test pilot following the latter's death whilst test-flying the DH.108 Swallow over the Thames estuary. He went on to test the de Havilland Comet, the world's first jet airliner which first flew in 1949. He also test flew the re-built Comet 3 and 4 in the late 1950s and the de Havilland (later Hawker Siddeley) Trident in 1962. He continued test flying Tridents, with another milestone being the first flight of the Trident 3 in 1969.

Cunningham had one serious accident whilst flying. On 20 November 1975 at Dunsfold Aerodrome, Surrey, a flock of birds was ingested by the engines on his HS-125 aircraft just after takeoff. The aircraft crashed and left the perimeter of the airfield where it collided with a car carrying six passengers who were killed. No-one died on board the HS-125. He remained chief test pilot at Hawker Siddeley (Hatfield) until 1978 when British Aerospace was formed. He was awarded the Segrave Trophy in 1978.

The autobiography of his most frequent airborne interception operator C.F. (Jimmy) Rawnsley, Night Fighter (co-authored by Robert Wright, published by Ballantine Books in 1957), includes vivid descriptions of several of Cunningham's battles and incidental biographical information about him.

In 2003 Cunningham was honoured with having a street named after him,[4] Cunningham Avenue is one of the main residential streets which make up Salisbury Village, a new development currently being built on the former de Havilland site in Hatfield. The former Addington Hotel, a pub in New Addington in Surrey, near Biggin Hill aerodrome, was named The Cunningham in his honour. Cunningham pulled the first pint at the renaming ceremony.

Since 2004 the Air Squadron, a UK flying club, has administered the John Cunningham Flying Scholarships, funded in part by his estate.

Group Capt John 'Cat's Eyes' Cunningham

12:02AM BST 23 Jul 2002

Group Capt John 'Cat's Eyes' Cunningham, who has died aged 84, was a night fighter ace and later a consummate test pilot whose name guaranteed the reputation of British aviation.

After destroying at least 20 enemy aircraft, Cunningham piloted the maiden flight of the Comet, which became the world's first passenger jet airliner.

When the plane was involved in a series of dramatic crashes, Cunningham took a model off the production line, and tested it to the point of destruction. He then ushered its amended successors into both airline and Service use.

The RAF's continuing employment of Nimrod, the Comet's maritime reconnaissance derivative, is a reminder of the debt owed to Cunningham for his lead in the exhaustive test programmes.

All this was far in the future when Cunningham, already a de Havilland junior test pilot and an Auxiliary Air Force weekend flier with No 604 (County of Middlesex) Squadron, was called up to full-time service shortly before the outbreak of war in 1939.

Equipped with the two-engine Bristol Blenheim, which had to search hopelessly for night raiders, Cunningham and his fellow pilots had little more to help them than training, eyesight and instinct.

"We didn't look on the so-called fighter version of the Blenheim as a very attractive aircraft," he recalled. "As we went off to war we thought 'We are not going to last long against the Me 109.' "

During the early stages of the Battle of Britain in 1940, Cunningham was relieved to be asked to experiment with a photo-electric bomb, devised to be dropped from above on heavy enemy bomber formations. When this project was abandoned, experimental airborne radar was beginning to become available for trial.

On the night of November 19 1940, Cunningham bagged his first Ju 88. After exchanging his make-do Blenheim for a two-engine Bristol Beaufighter he shot down a Heinkel 111 bomber over the Channel and another over Lyme Bay.

As Cunningham's score mounted the story was spread that his success owed much to a hearty consumption of carrots, which were said to sharpen his eyesight; and henceforth he was known as "Cat's Eyes".

The deception, which was aimed at the enemy, also helped Lord Woolton, the food minister, to get across the value of vegetables, particularly carrots, in the rationed wartime diet.

No allusion was made to the primary reason for Cunningham's success, the introduction of airborne radar and its operators; Jimmy Rawnsley, Cunningham's re-trained air-gunner, was one of the best.

Cunningham later mused: "It would have been easier had the carrots worked. In fact, it was a long, hard grind and very frustrating. It was a struggle to continue flying on instruments at night.

"The essential was teamwork - not just between pilot and radar operator. A night fighter crew was at the top of a pyramid, ground control radar and searchlights at the base, and up there an aircraft with two chaps in it. Unless they were competent and compatible all that great effort was wasted."

In mid-April 1941, Cunningham and Rawnsley destroyed three enemy bombers in one night, and when Cunningham left 604 for a staff appointment, the squadron had shot down twice as many enemy aircraft as any other night fighter unit.

Cunningham returned to operations early in 1943, when he received command of No 85, a Mosquito night fighter squadron. After adding several more kills to his score - including four fast FW 190 fighter bombers - Cunningham joined Fighter Command's No 11 Group headquarters as a group captain aged 26, still with a baby face and twinkling blue eyes.

John Cunningham was born on July 27 1917, the son of the company secretary of the Dunlop Rubber Company. At nine, he had a joyride in an Avro 504 biplane, and was immediately captivated by the idea of flying. His ambitions were further stimulated at Whitgift School by its proximity to Croydon airport. He then joined the de Havilland apprenticeship scheme.

This early association with de Havilland gave Cunningham a head start when, as the war ended, he opted to pass up the opportunity of a glittering peacetime career in the RAF and return to civil aviation.

Exchanging a group captain's brass hat for a test pilot's overalls, he took over flight development of the company's Goblin turbojet engine. Within a year the death, in a crash, of Geoffrey de Havilland, son of the company's founder Sir Geoffrey de Havilland, cleared the way for Cunningham to become the company's chief test pilot.

Cunningham took over the major responsibility for investigating the characteristics of the single-seat DH 108's swept-wing design and also for obtaining basic data for the future DH 106 Comet and the naval fighter Sea Vixen.

Meanwhile, work had started on the Comet, and Cunningham, accompanying BOAC crews on five transatlantic flights and two round trips to Australia, also began to gain experience of the requirements of airline crews.

On July 27 1949, his 32nd birthday, he was conducting taxiing trials when, with no fuss, he made an unannounced 35-minute maiden flight. But within three years de Havilland began to pay the price of hastening the Comet into service.

On October 26 1952, a BOAC Comet taking off from Rome failed to become airborne; there were no casualties, but the aircraft was damaged beyond repair.

Although the pilot was wrongly blamed, Cunningham was not satisfied. But his exhaustive take-off tests proved fruitless; and the accident was repeated the following March when a Canadian Pacific Airlines Comet was destroyed at Karachi.

In each accident, as Cunningham was to discover, the nose had lifted too high too early, resulting in a great increase in drag. Following further tests, the leading edge of the wing was revised, along with Cunningham's advice on take-offs to pilots.

Despite a further take-off accident in May, when a BOAC Comet crashed shortly after take-off from Calcutta due to poor weather, all was fairly plain sailing until January 1954, when the first production Comet disintegrated at 35,000 feet off Elba.

In April a similar break-up took place south of Naples over the volcanic island of Stromboli, and it was decided to test an entire Comet fuselage for fatigue in a water tank at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough.

Although Farnborough's findings centred on the fatal flaw of metal fatigue in a pressurised hull, the likelihood of potential disaster had arguably been heightened by design shortcuts and economies which had been made to ensure that the Comet became the world's first passenger jet.

Cunningham immediately busied himself with remedial action. He flew to Canada to bring back two RCAF Comet 1As; and after their fuselages were rebuilt took them home again.

In December 1955, Cunningham made a world tour, in which Comet III's performance was flawless. The next year President Eisenhower presented him with the Harmon Trophy, the highest American honour for services to aviation, in recognition of his contribution to jet transport.

Honour was slower at home; and he was not elevated to the de Havilland Board until 1958 when BOAC put Comet IV on to the London-New York route.

When, during this period, de Havilland became a division of Hawker Siddeley, Cunningham, always ready to get on with the job in hand, was not fazed. Sir Geoffrey de Havilland noted that Cunningham, a bachelor, was "test pilot, demonstration pilot and ambassador all in one and has made some sensational flights. He can do thousands of miles for many days and at the end of the flight can be charming, unruffled and apparently as fresh as ever when discussing points raised by a host of officials, Pressmen and others."

While Trident, which was to become so successful with British European Airways and elsewhere, was on the way in 1960 and 1961, Cunningham remained busy testing Comet versions.

Eventually he was involved with Trident's initial trials and with colleagues saw it through more than 1,800 hours of testing before the first Trident was certified airworthy in 1964.

One of Cunningham's greatest assets was his relationship with overseas buyers and his talented training of foreign pilots. After delivering Tridents to Pakistan he became extremely busy with a substantial order for China.

From 1972 he began to deliver Tridents, one by one, to Kwangchow. Part of the deal was that he had to do a test flight with a Chinese crew on each aircraft from Kwangchow to Shanghai.

So far, other than a 1939 bale-out from a Moth Minor, Cunningham had led a charmed life; but in 1975 he was piloting a DH 125 executive jet, conveying a party of Chinese visitors from the Hawker Siddeley airfield at Dunsfold to Hatfield, when a huge flock of plovers was ingested by his engines.

Barely off the runway, Cunningham touched down at some 130 mph. The jet shot across a road, colliding with a car and killing four passengers before halting in a field where it caught fire.

Cunningham sustained two crushed vertebrae, but none of his passengers were killed, and within a year he resumed flying. Trident deliveries to China had three years to run and his Chinese customers asked him to see the contract out.

Cunningham remained chief test pilot after Hawker Siddeley had been merged into British Aerospace, where he was an executive director from 1978 until he retired in 1980.

With more time available, he enjoyed looking after the grounds of his home, not far from the former de Havilland airfield and factory in Hertfordshire, and devoted much time and effort to the nearby museum housing the prototype Mosquito and other historic de Havilland equipment and memorabilia.

He also supported fundraising efforts for a variety of organisations. These included the RAF Benevolent Fund, the de Havilland Flying Foundation and the Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire Aircrew Association and 604 and 85 Squadron associations, of which he was president.

Additionally, Cunningham was a Liveryman of the Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators and much involved with the Battle of Britain Fighter Association and a staunch supporter of the RAF Club.

It was the more unfortunate that, following the collapse of Lloyds in 1988, he was faced with heavy financial commitments having been a Name in the organisation. Even though he re-mortgaged his property and was left with a much reduced income, he remained buoyant in the face of illness.

Cunningham was appointed OBE in 1951 and CBE in 1963. He was awarded the DSO in 1941 and Bars in 1942 and 1944; the DFC and Bar in 1941, also the Air Efficiency Award (AE). He also held the Soviet Order of Patriotic War 1st Class and the US Silver Star.

Cunningham was Deputy Lieutenant for Middlesex in 1948 and Greater London in 1965. He was awarded the Derry and Richards Memorial Medal in 1965, the Segrave Trophy in 1969 and the Air League Founders Medal in 1979.

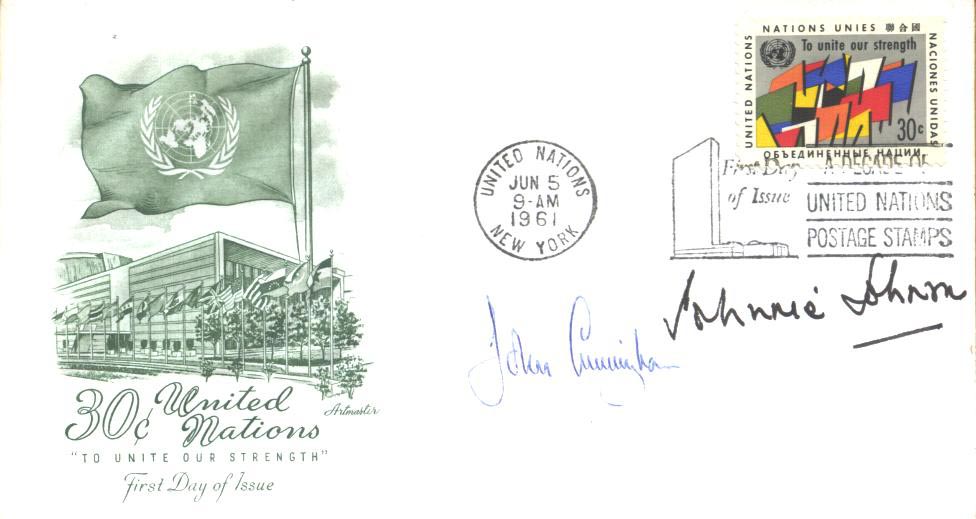

Signed First Day Cover signed by both Johnson and Cunningham

Price: $45.00

Please contact us before ordering to confirm availability and shipping costs.

Buy now with your credit card

other ways to buy

|