|

~SOLD~ LORD LOVAT

Lord Lovat

In the whole of the six long years of the Second World War, Lord Lovat served hardly more than six days in action. And yet he became universally known and accepted as a great war hero.

How, one wonders, could that possibly be? Perhaps quite simply: his was an inspirational personality. Under him, men did more than they could possibly imagine they could do, were braver than they knew themselves to be. Lovat seemed to impersonate a 20th-century Robin Hood, or perhaps more realistically a Rob Roy. With him there lay danger, but also high adventure. He led No 4 Commando group on the raid on Dieppe in 1942, and No 1 Commando Brigade in the D-Day landings in June 1944.

My first close encounter with Lovat was when I was posted to 1st Commando Brigade HQ, stationed at Cowdray Park, Midhurst, in 1943. I was to be his staff captain.

Lovat was standing with his back to the fire, in the big lounge which acted as our officers' mess, chatting to a group. But as soon as I entered he spotted me and called out - "Hey you, you're my staff captain, but I can tell you this, if you're no bloody good you'll be out on your arse before you even know you've started."

Lovat did not have to shout at anyone, his normal speaking voice could have carried across a crowded ballroom. The voice and his stunning good looks were the first thing that struck one.

He had joined the commandos, some time in 1940, after a disagreement with his CO in the Lovat Scouts. When he left he took some of his best men with him. And some of them ended up with him in No 4 Commando. By 1942 he had command of his unit, which, with No 3 Commando, was chosen for the Dieppe landing.

Lovat was no conventional regular soldier. Indeed he was quite the reverse. But he knew how to pull a unit together and enthuse the men with his unique form of leadership. He was demanding. He trained his men intensely. He was completely intolerant of inefficiency. And ruthless when he had to be. He had me, so to speak, on my toes from the word go. It was like that with everyone. But, withal there was a debonair, almost romantic air about him, which intrigued and brought the best out of one.

In the Dieppe raid, his plan for the capture of the Varengeville battery was masterly. And proved brilliantly successful. Yet he had to fight the orthodox planning from above tenaciously to get his His was the choice of the landing beaches. And the successful scaling of the formidable cliffs and the fierce bloody attack and hand-to-hand fighting to take the battery were a model of what a commando raid from the sea could be. Every gun was silenced. And although the main attack on the harbour was a disaster, it could have been much worse if the guns had not been so successfully silenced.

When the brigade began its preparation for the D-Day landings he devoted himself almost entirely to training. And when eventually No 1 Commando Brigade landed on Sword Red Beach it was probably as perfect a fighting force as could be found anywhere. By "D" plus Six, after more than four days' continuous fighting, Lovat was desperately wounded. He calmly handed over, gave orders that not a step back should be taken, then called for a priest and was evacuated. Those who saw him then could not believe he could possibly survive.

At Sword Beach he had landed his small Tac HQ with one unit at "H" plus 30 (30 minutes after zero hour), while the rest of the brigade followed on some 40 minutes later. Nearly half his band were casualties before we even landed. He took an appalling risk, but no one queried it. Scrambling up the battle- littered beach to join him, we crouched beneath the 80lb Bergen rucksacks and, we hoped, beneath of the flak the enemy were hurling at us. When we reached the sand-dunes at the top of the beach I looked up and saw Lovat standing, completely at ease, taking in the scene around him. Instinctively I stood up straight and reported all ready and correct. With a nod he turned on his heel and led Brigade HQ inland towards Pegasus Bridge and, as it happened, slap through a wired- off area, clearly marked minefields. We followed literally in his footsteps.

Under fire, he seemed to be completely at ease; almost contemptuous of the enemy's worst efforts. Of course he was not really so. He was highly intelligent and knew full well what danger he might be in. In charge alone by "D" plus Four, after seemingly endless shelling and attack, with nearly one-third of the brigade casualties, he knew better than any one of us how near we were to annihilation.

Gay, debonair, inspirational, and yes, lovable - arrogant, ruthless, at times terrifying, his personality is too complex to explain. Perhaps we should not try to, and simply remember that he was a Lovat.

Max Harper Gow

Shimi Lovat's military background ran back through generations of Frasers, including Simon Fraser, known as the Patriot, hung drawn and quartered at Tower Hill at Edward I's orders, and Simon Lovat, beheaded after the 1745 rebellion, writes Louis Jebb.

His father, Simon Fraser, 16th Lord Lovat, was himself a distinguished soldier, raising the Lovat Scouts in the South African War, and commanding the Highland Mounted Brigade during the First World War. In the same war the infant Shimi lost three uncles killed at the front as well as his godfather, Julian Grenfell, author of the celebrated war poem "Into Battle".

The Master of Lovat, as he was styled in his father's lifetime, was educated by Benedictine monks at Ampleforth College, in Yorkshire, and at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he studied history. His father died in 1933 at a point-to-point meeting near Oxford, where Shimi had won a race earlier in the day, leaving him to inherit the title, the chiefdom of the Clan Fraser of Lovat, and an estate in Inverness-shire amounting to nearly 200,000 acres. He was 22.

His parents had made Beaufort Castle, overlooking the river Beauly, not just the seat at the heart of this great Scottish estate, but a second home for diverting visitors including Fr Ronald Knox, a brilliant scholar and for many years the Roman Catholic chaplain at Oxford University who came to Beaufort for his leave, and the novelist Maurice Baring, like Knox a convert to Roman Catholicism who spent much of the summer at Beaufort writing in the Twenties and Thirties.

Shimi and his siblings delighted in their company (the ebullient Baring encouraged them, in fact bribed them, to behave as badly as possible at meal-times). The two elder of Shimi's sisters, Magdalen and Veronica, were known as Catholic beauties of their day; Magdalen married to the Earl of Eldon and Veronica first to Alan Phipps, killed in action in 1943, and then to the writer Sir Fitzroy Maclean, and herself a journalist, cookery writer and editor. His younger brother Hugh, no less glamorous a figure than Shimi and with just as commanding a voice, made his name in politics, as Conservative MP for Stone and a government minister. And then there was their sister Rose, who died at the age of 14 and whose extraordinary character and spirituality is caught in a passage from Shimi Lovat's autobiography, March Past (1978), and in the poem "Rose" dedicated to her by her godfather Hilaire Belloc.

As they travelled as children on the train to the highlands, their mother, Laura, would read to them Scottish tales and legends and teach them the names of the places they passed. The atmosphere at Beaufort at the time is well caught in her own book Maurice Baring: a Postscript (1947), which takes the story up to the Second World War when Baring moved to Eilean Aigas, a house on an island in the river Beauly, where Laura Lovat nursed Baring to his death in 1945, and where he acted as a wise comfort to the family's grief after Rose's death and that of Alan Phipps and, as Lovat puts it in his autobiography, "an inspiration to the younger generation in uniform".

Lovat's career in uniform dated back to 1932, when he joined the Scots Guards immediately after university. He left the army in 1937, and took Beaufort over from his mother the following year, after his marriage to Rosamond Delves Broughton. Tragically, much of the treasures of Beaufort were destroyed at this time in a catastrophic fire that gutted the picture gallery and the library.

With the outbreak of war, he joined the Lovat Scouts, the regiment his father had founded, before transferring to the groups which were formed into the commandos. In 1941, the year before the raid on Dieppe, Lovat led his commandos on the raid on theLofoten Islands, off Norway, sinking 12 ships, destroying factories and setting fire to petrol and oil depots. He was awarded the Military Cross for his part in a reconnaissance raid on Boulogne and the DSO after the raid on Dieppe, and promoted lieutenant- colonel in 1942 and Brigadier in 1943.

Lovat was appointed Joint Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs in the caretaker government in 1945, but forsook politics at the end of that year to devote himself to forestry and breeding shorthorn cattle at Beaufort. He travelled widely on clan business and for big-game hunting, and spoke on Highland affairs in the House of Lords. In the 1960s he made over Beaufort Castle and most of his estates to his eldest son, Simon, Master of Lovat, as a hedge against inheritance tax or the chance of his repeating his father's early demise.

One of the heroes of Shimi Lovat's autobiography is his maternal grandfather, Tommy Lister, fourth Lord Ribblesdale, Master of the Queen's Buck Hounds, who was the subject of a famous portrait by John Singer Sargent: a tall, slim figure in full hunting fig and top hat set at a raffish angle. "In his patrician looks," Lovat writes, "lay the essence of nobility". And there is a striking similarity in the figures cut by grandfather and grandson. Lovat also touches on his mother's inheriting from her father his European tastes, his classic looks, slim figure and long tapering hands.

In the last 12 months of his life he needed to match his mother's staunch resignation in the face of tragedy - she lost two brothers in the First World War, a husband young, as well as a son-in-law and beloved daughter during the Second. A year ago Lovat's youngest son, Andrew Fraser, was killed by a charging buffalo while on safari in Africa, while his eldest son, Simon, died of a heart attack a fortnight later. After the latter's death it was revealed that he had suffered serious business losses and left large debts on the Beaufort estates that have been for so long associated with the name of Lovat.

Simon Christopher Joseph Fraser, soldier, landowner: born 9 July 1911; styled 1911-33 Master of Lovat; succeeded 1933 as 17th Lord Lovat and 24th Chief of Clan Fraser of Lovat; DSO 1942; MC 1942; DL 1942; JP 1944; married 1938 Rosamond Delves Broughton (two sons, two daughters, and two sons deceased); died Beauly, Inverness-shire 16 March 1995.

MAX HARPER GOW/LOIUS JEBB

Sunday 19 March 1995

Lord Lovat: he was a giant among giants on D-Day

The Fraser clan were proud to erect a new memorial to Lord 'Shimi’ Lovat, who led the Commandos ashore on Sword Beach

There were 200 of us at Ouistreham on Sword Beach – Fraser family and clan, French and British dignitaries, a Scots Guards piper, standard bearers and a few veteran French commandos. We were gathered in Normandy to unveil a bronze statue in memory of my father-in-law, Brigadier Lord Lovat, Commander 1st Commando Brigade, and all those who served under him, including 200 Free French.

Shimi’s leadership qualities were tested to the limit on D-Day. The mission of 1st Commando Brigade – or 1st Special Service Brigade, as it was known in June 1944 – was to break through German defences on the eastern side of Sword Beach. At lightning speed, they were to fight their way four miles inland to Pegasus Bridge over the Caen Canal, and bring reinforcements to the 6th Airborne Division, relieving the glider-borne troops who had taken the bridge at dead of night.

Shimi and his commandos arrived just after the appointed hour of midday, to the swirl of pipes. He famously apologised for being two minutes late. The bridges were crucial; at the push of a detonator, the Germans could have destroyed them. With the Allied supply lines cut, the invasion could have foundered.

Plunging into further battles, Shimi was nearly killed four days later by Allied shrapnel and was given the last rites by Father René de Naurois. His last words as he handed over his brigade were: “Take over the Brigade and not a step back; not a step back!”

Members of the de Naurois family joined us at the unveiling ceremony. Afterwards, Arlette Gondrée, whose family owns the café beside Pegasus Bridge, hosted a lunch for us all. Her parents helped those who resisted the German occupation and, as a young child, she lived with an acrid smell of skin, cordite and blood as the wounded were carried in secret on to the kitchen table.

She remembers D-Day vividly; playing in the garden beside the canal, hearing Millin’s bagpipes as they came ever closer. The French had been so traumatised by the Occupation but it dawned on her, even at the tender age of five, that this was an extraordinary moment. Perhaps the end of hunger was in sight.

Her father started digging up the champagne that he had hidden from the Germans – 1,000 bottles in all. As Shimi arrived, during a lull in the crossfire, he was offered a glass. He thanked his host profusely but declined, explaining he was at work.

Arlette’s cafe has become her personal shrine to D-Day. She is the keeper of her own archives, photos and memorabilia; her walls are covered with photos of the heroes she admires so much. Hers is a sacred mission: to explain to young visitors what sacrifice a whole generation made for the freedoms we enjoy today, and to keep their memories alive. And it is thanks to her, and the community of Ouistreham, that the statue of Shimi is standing so proudly today in the memorial garden on Sword Beach. But it was one small boy in Los Angeles who ignited the project.

I was in California with my eight-year-old grandson, Roscoe, and we were watching The Longest Day, the Hollywood classic that tells the story of D-Day (Peter Lawford plays Shimi). Roscoe expressed a wish to see where his great-grandfather had landed.

In May 2013, we trooped off to Normandy and remet Arlette Gondrée. She immediately told me that Leon Gautier, president of the 4th Commando Association, a Free French fighter who landed with Shimi, wanted the Fraser family to raise money for a statue of Shimi in time for the 70th anniversary celebrations. So, too, she added, did the people of Ouistreham.

Time was very short. We had only eight months before the sculpture had to be in the foundry. With the help of family, friends and clan members, we managed to raise the five-figure sum required for the commission. Over five, or was it six, trips by ferry to France, I first persuaded the local mayor to give his blessing, then chose the spot for the plinth, and made other arrangements, including making sure that Leon Gautier could be there at the unveiling.

Four weeks before the planned date there was a huge lurch to the Right in the local elections and the mayor was ousted. In fear for our carefully laid plans, my sister-in-law and I rushed over once more to meet the new incumbent, Monsieur Bail, just 28. All was well, he reassured us, but he was distracted. Ouistreham was planning something far bigger – the 70th anniversary commemorative visit of so many world leaders.

Today, Shimi will be standing guard alongside them, facing three-quarters towards France and a quarter back to Britain. I couldn’t have had him turning his back on us. Nor us on him, and the many like him who on D-Day dedicated their lives so we could have ours.

Lord Lovat (1911-1995) died at Beauly, Inverness-shire

It is a magnificent spot – the garden well-tended, the sands golden – and, on the day we gathered there, the sea glimmered. As the veil was gently drawn from the statue, a Fraser cousin read those famous lines from the Commando prayer: “Teach us to give and not to count the cost/ To fight and not to heed the wounds/ To toil and not to seek for rest ... We will remember them.” There wasn’t a dry eye among us.

I had been very keen that the young be included in this gathering of the clan. And so 35 scampering Fraser children, dressed in tartan trews and kilts, along with the family terrier, a tartan ribbon in his collar, all stood still at that moment.

I pictured Shimi, on the eve of D-Day, then 32, addressing his troops after prayers. The service was over, and the men had been kneeling on sodden turf in driving rain in a Hampshire field. “I wish you all the best of luck in what lies ahead,” he had told them. “This will be the greatest military venture of all time; the Commando Brigade has an important role to play and 100 years from now your children’s children will say, 'They must have been giants in those days’.”

Our thoughts also turned to a generation of tough, brave young men, only a little older than our scampering children. They had leaped into those icy seas on D-Day, sometimes out of their depth and unable to swim, bowed down by their mountainous backpacks. They had fought their way up the beaches, seeing friends being blown to smithereens around them. Operation Overlord had begun. These indomitable young men had come to liberate Europe.

As 24th Chieftain of Clan Fraser, Shimi – MacShimidh to give him his Gaelic title – was born into leadership. It was in his genes (David Stirling, his cousin, founded the SAS). Resilient, tough, charismatic, he believed in public service and in serving his country, but he also had a literary, almost poetic bent. Commanding and dashing, he exuded confidence that instilled courage in those around him.

“The handsomest man to cut a throat” was how Winston Churchill once described him. He had the best posture of anyone I have met. Ian Rank-Broadley’s sculpture captures it brilliantly. We chose Ian for the commission because he is first and foremost a military sculptor, with real knowledge and understanding of fighting men and women. His work at the Armed Forces Memorial in Staffordshire is remarkable.

The statue is in a small memorial garden, no bigger than the German bunker that stood on the spot 70 years ago. There, at 6.50am on June 6 1944, “Shimi” Lovat led his men into battle on D-Day, all of them buoyed by his personal piper, Bill Millin, playing Highland Laddie and Scotland The Brave.

The unveiling took place last month. In an ideal world, it would have happened on the precise anniversary, but the garden is small and today will play host to the Queen, President Obama, Chancellor Merkel, Prime Minister Cameron and President Putin as they pay tribute not just to Shimi and his men, but to all of those who gave their lives.

By Virginia Fraser

7:00AM BST 06 Jun 2014

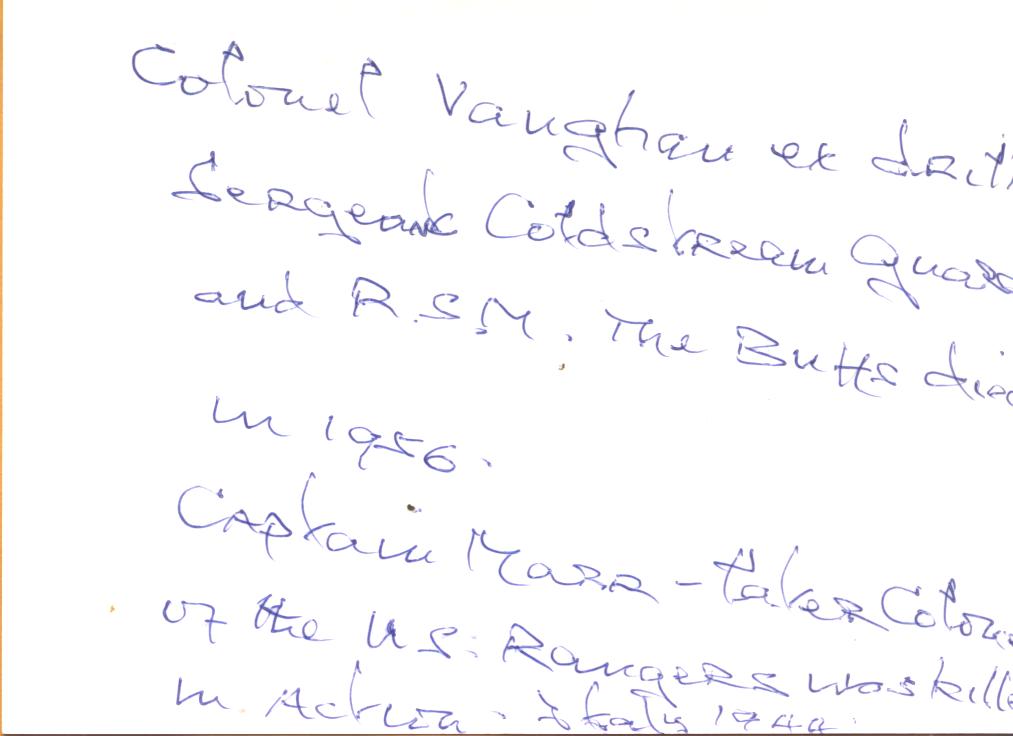

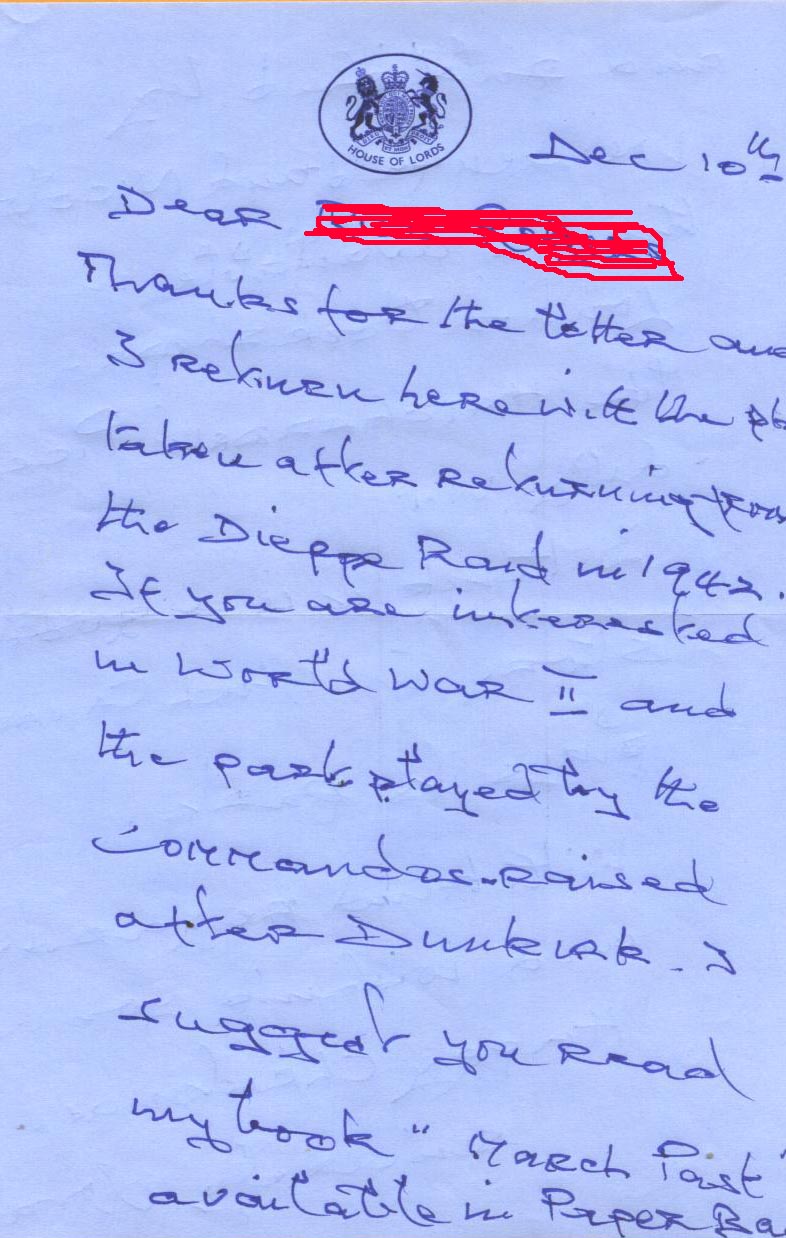

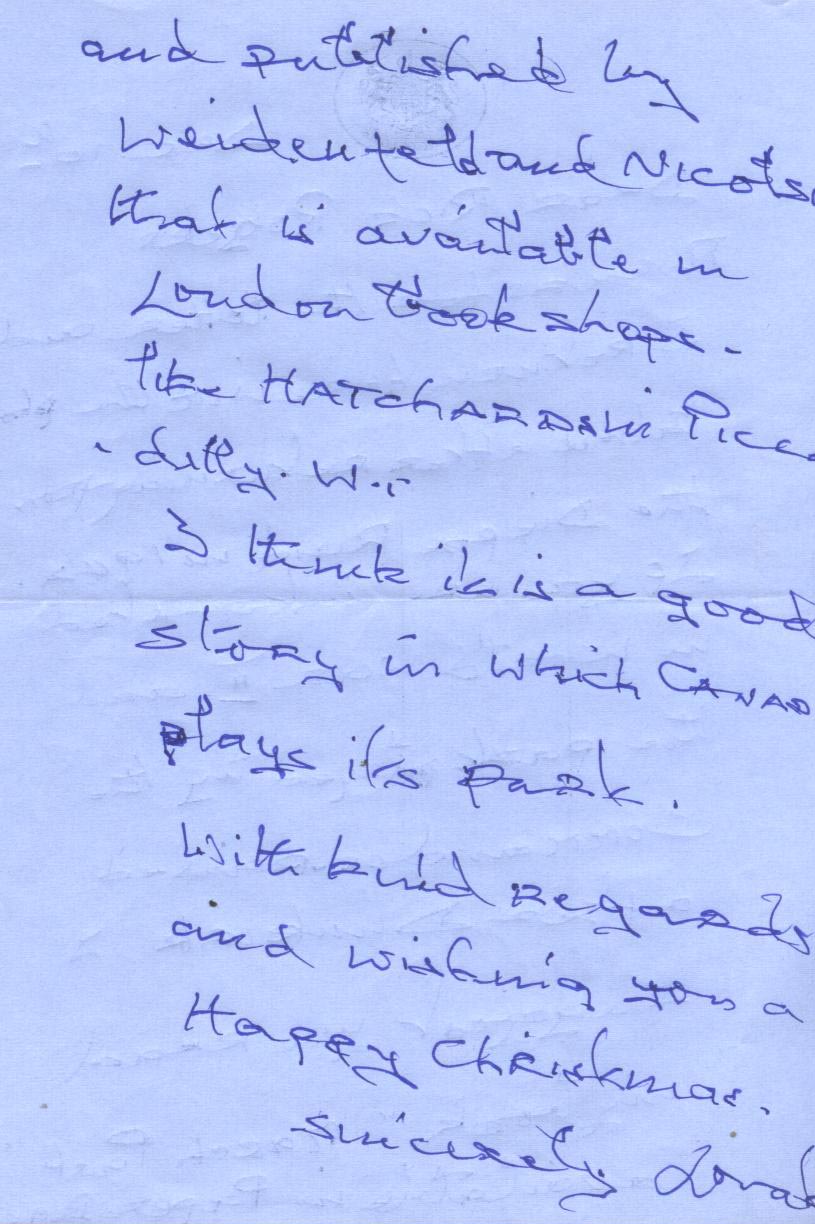

Signed photo and letter (red marking is for censor only not on letter)

Price: $0.00

Please contact us before ordering to confirm availability and shipping costs.

Buy now with your credit card

other ways to buy

|