|

~SOLD~ HACKETT John Winthrop

Brigadier John Winthrop Hackett

Unit : Headquarters, 4th Parachute Brigade

Army No. : 52752

Awards: Knight Grand Cross, Commander of the British Empire, Distinguished Service Order and Bar, Military Cross, Twice Mentioned in Dispatches, BLett, MA, LLD, DL

General Sir John Winthrop Hackett, GCB, CBE, DSO & Bar, MC (5 November 1910 – 9 September 1997) was an Australian-born British soldier, painter, university administrator, author and in later life, a commentator.

Early life

Hackett, who was nicknamed "Shan", was born in Perth, Western Australia. His Irish Australian father, also named Sir John Winthrop Hackett (1848–1916), originally from Tipperary, was educated at Trinity College, Dublin (B.A., 1871; M.A., 1874), and migrated to Australia in 1875, eventually settling in Western Australia in 1882 where he became a newspaper proprietor and editor, and a politician. His mother was Deborah Drake-Brockman. Her parents were prominent members of Western Australian society: Grace Bussell, famous for rescuing shipwreck survivors as a teenager and Frederick Slade Drake-Brockman, a prominent surveyor and explorer. Deborah had three sisters and three brothers.

On 3 August 1905, aged 57, Hackett senior married eighteen-year-old Deborah Drake-Brockman (1887–1965)—later Deborah, Lady Hackett; Deborah, Lady Moulden; and Dr Deborah Buller Murphy—a director of mining companies. They had four daughters and son. Hackett senior died in 1916. Lady Hackett remarried in 1918 and moved to Adelaide to live.

Hackett junior received secondary schooling at Geelong Grammar School in Victoria, after which he travelled to London to study painting at the Central School of Art. He then studied Greats and Modern History at New College, Oxford, earning an M.A. As his degree was not good enough for an academic career, Hackett joined the British Army and was commissioned into the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars in 1933, having previously joined the Supplementary Reserve of Officers in 1931. During his military training he completed a thesis in history with focus on the crusades and the early Middle Ages, particularly Saladin’s campaign in the Third Crusade, for which he was awarded a B. Litt. He also qualified as an interpreter in French, German and Italian, studied Arabic, and eventually became fluent in ten languages.

He served in Mandate Palestine and was mentioned in despatches in 1936, and then with the Trans-Jordan Frontier Force from 1937–1941 and he was twice mentioned in despatches.

Second World War

Hackett fought with the British Army in the Second World War Syria-Lebanon campaign, where he was wounded and as a result of his actions was awarded the Military Cross. During his recovery in Palestine he met Margaret Fena, the Austrian widow of a German. Despite the difficulties involved, he persisted and eventually gained permission from the authorities; they married in Jerusalem in 1942.

In the North African campaign he commanded 'C' Squadron of the 8th Hussars (his parent unit) and was wounded again when his Stuart tank was hit during the battles for Sidi Rezegh airfield. He was severely burnt when escaping the stricken vehicle. He received his first Distinguished Service Order for this event. Whilst recuperating at GHQ in Cairo he was instrumental in the formation of the Long Range Desert Group, the Special Air Service and Popski's Private Army.

In 1944, Hackett raised and commanded the 4th Parachute Brigade for the Allied assault on Arnhem, in Operation Market Garden. In the battle at Arnhem Brigadier Hackett was severely wounded in the stomach, was captured and taken to the St. Elizabeth Hospital in Arnhem. A German doctor at the hospital wanted to administer a lethal injection to Hackett, because he thought that the case was hopeless. However he was operated on by Alexander Lipmann-Kessel, who with superb surgery managed to save the brigadier's life.

St Elizabeth Hospital

After a period of recuperation, he managed to escape with the help of the Dutch underground. Although he was unfit to be moved, the Germans were about to move him to a POW camp. He was taken by 'Piet van Arnhem', a resistance worker from Ede, and driven to Ede. They were stopped on the way but Hackett had extra bloody bandages applied, to make him look even worse than he was. Piet told the checkpoint that they were taking him to hospital. They were let through despite the hospital being in the opposite direction, from which they had just come.

He was hidden by a Dutch family called de Nooij who lived at No. 5 Torenstraat in Ede, an address that no longer exists due to development. The de Nooij family nursed the brigadier back to health over a period of several months and he then managed to escape again with the help of the underground. He remained friends with the de Nooij family for the rest of their lives, visiting them immediately after they were liberated, bearing gifts. Hackett wrote about this experience in his book I Was A Stranger in 1978. He received his second DSO for his service at Arnhem.

Post-war career

He returned to Palestine in 1947 where he assumed command of the Trans-Jordan Frontier Force. Under his direction the force was disbanded as part of the British withdrawal from the region. He attended university at Graz as a postgraduate in Post Mediæval Studies.[1] After attending Staff College in 1951 he was appointed to command the 20th Armoured Brigade and, on being promoted to Major General, assumed command of the 7th Armoured Division.[1] In 1958 he became Commandant of the Royal Military College of Science, Shrivenham, and was promoted to Lieutenant General in 1961. He became General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Northern Ireland Command in 1961[9] and was knighted (KCB) on 2 June 1962.[10] In 1963, he was appointed to Ministry of Defence as Deputy Chief of the General Staff, responsible for forces organisation and weapon development and became the leading figure in the reorganisation of the Territorial Army, something which made him unpopular. He relinquished his appointment as Deputy Chief of the General Staff on 4 February 1966. On 14 April 1966, he was appointed command of the British Army of the Rhine and the parallel command of NATO's Northern Army Group, but his ability to speak several languages made him a natural choice, as did his friendship with foreign soldiers such as General Kielmansegg of the Bundeswehr. In 1968 he wrote a highly controversial letter to The Times, critical of the British Government's apparent lack of concern over the strength of NATO forces in Europe but signed the letter as a NATO officer, not as a British commander.

After retirement from the Army, Sir John continued to be active in several areas. From 1968 to 1975 he was Principal of King's College, London. He proved to be a popular figure, addressing gatherings of students on several occasions, and attending at least one NUS demonstration for higher student grants.[citation needed] In 1978, Sir John wrote a novel, The Third World War: August 1985, which was a fictionalized scenario of the Third World War based on a Soviet Army invasion of West Germany in 1985. It was followed in 1982 by The Third World War: The Untold Story, which elaborated on the original, including more detail from a Soviet perspective. The American author Max Brooks has cited Hackett's work as one source of inspiration for the latter's World War Z novel.

His (British) military decorations included the Knight Grand Cross of the Bath, Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Distinguished Service Order and Bar, Military Cross, and six times Mentioned in Dispatches. His obituary in The Times called him a man of "intellect and prodigious courage.”

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

The 33 year old Brigadier Hackett was Irish by blood, but was born in Perth, Australia, the son of a wealthy newspaper proprietor. His Irish relations called him Shaun, but this was changed to Shan by his Liverpudlian nanny and the nickname stuck. Educated at Oxford, Hackett was a highly proficient historian, linguist, and classicist. Commissioned into the 8th (King's Royal Irish) Hussars upon joining the army, his service took him to Syria in 1940, where he was wounded, and to North Africa in 1942, where he was again wounded and suffered burns when his Stuart Tank was hit during Rommel's first desert offensive. When recovered he held a staff posting in Cairo before being given command of, and the task of raising, the 4th Parachute Brigade in the Middle East.

Hackett was short in stature, but had a great intellect and a bold, decisive attitude. He was also in the highly beneficial position of having earned the complete loyalty and trust of everyone in his Brigade. His men noted that he didn't appear to carry a mess kit; he ate when they ate, and if they went hungry then so did he.

Along with several others, Hackett objected strongly to Operation Comet, the forerunner of Market Garden, on the grounds that the 1st Airborne Division was not strong enough to single-handedly capture and hold all of the objectives, from Eindhoven to Arnhem, and his view that it would have been a complete disaster for all played a significant part in its cancellation. With the addition of the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions to deal with the Eindhoven and Nijmegen areas, he was much happier with the Market Garden plan, though the weaknesses in the air plan were blatantly apparent to him. He later said, "The airborne movement was very naive. It was very good on getting airborne troops to battle, but they were innocents when it came to fighting the Germans when we arrived. They used to make a beautiful airborne plan and then added the fighting-the-Germans bit afterwards." Yet he was happy with Market Garden, and he recognized that it was vital to get the Division into battle after all the demoralizing cancellations imposed upon them during the recent months. He was adamant that troops of such quality could not be constantly subjected to such frustration and he believed that they had to be got into a battle, almost at any price. Years later, however, he reflected that it was nonsensical to drop his Brigade into Arnhem twenty-four hours after the first landings, when all surprise had been lost. He concluded that Market Garden was doomed before it had begun.

Major-General Urquhart, upon attending one of the 4th Parachute Brigade's briefings, joked that if all went well then Hackett and his men would arrive in time to see "B" Echelon of XXX Corps pass over Arnhem Bridge. After the General left, Hackett brought the atmosphere crashing down to earth by adding, not wishing to disagree with Urquhart, but if 50% of the Brigade were alive and fit for duty after a few days of the operation commencing, then he would be happy. As it turned out, this casualty assessment was eerily accurate.

En route to Arnhem on Monday 18th September, Brigadier Hackett was in good cheer and promised his American pilot a bottle of champagne if his stick was dropped on target. The pilot had a remarkably cool hand, and Hackett was dropped within a mere 300 yards of his exact target area. Hackett had the honour of presenting him with his reward when the two next met in 1989.

As a consequence of the communications blackout in the Arnhem area, Hackett had no reason for concern about the drop, and he expected that it would be unopposed, leaving his men able to go about their business without much initial fuss. As the formation approached DZ-Y, however, he was naturally surprised to discover that the heath land around the zone was on fire and that a battle appeared to be raging all around to prevent the Germans from overrunning it. During his descent, Hackett let go of his walking stick, and when he reached the ground his first concern was to find it. He had not gone far before he was confronted with a group of 10 Germans, whom, he noticed, were only a little less terrified than he was at their meeting. They appeared eager to surrender, however, but he first made them wait while he found his stick before he marched them away.

When Hackett reached his Headquarters he was met by the Brigade Major, Major Dawson, who had arrived with the Advance Party on the First Lift, and was informed that Major-General Urquhart was missing and Brigadier Hicks had taken command of the Division in his absence. He was also told that Hicks had decided to detach the 11th Battalion from Hackett's command to send them into Arnhem with all speed to give support to the 1st Parachute Brigade, who was clearly in considerable difficulty. Hackett was not at all pleased about any of this news. To him, it was quite shocking that one of his battalions should have been seemingly selected at random, without any regard to casualties it may have suffered during the drop, and that he had been denied the common courtesy, as Brigade Commander, of deciding which unit was to be detached. Nevertheless, Hackett realized that of his three battalions, the 11th had landed closest to Arnhem, and so it was only sensible that they were chosen, so he ordered them on their way without further ado.

The remainder of the Brigade, meanwhile, pushed on eastwards in accordance with their original plan, and by nightfall Brigade HQ was established at the Buunderkamp Hotel, north of the railway line and to the south-west of LZ-L. Hackett asked the proprietor for all the mattresses that he had available, and so Headquarters slept on them outside, next to the wreckage of a glider that still had its dead pilot strapped into his seat.

Brigadier Hicks had asked that Hackett come to Divisional Headquarters as soon as possible, however it was not until near midnight that he was finally able to get away. He was unhappy that Hicks was in command of the Division because, although Hackett was by far the younger, his commission was senior to that of Hicks and so he should have precedence. Major-General Urquhart, although he had never felt it necessary to explain the situation to either of them as it seemed rather far fetched that both he and his acknowledge deputy, Brigadier Lathbury, should both be out of action at the same time, had preferred Hicks because he had far more experience of handling infantry, whereas Hackett was a cavalryman by trade. Furthermore, the situation at Arnhem was more in Hicks' favour as he had been on the ground for 24 hours and so was much more in touch with the general situation. Hackett, however, felt that the battle was progressing in a most unsatisfactory fashion at this time, as it appeared to consist of small, scattered groups of men fighting their own private battles all over the general area, without any thought of coordination or a clear objective. Hackett concluded that it was "a grossly untidy situation."

At about midnight on Monday 18th September, Hackett arrived at Divisional HQ and put these points very bluntly to Hicks. The two men were good friends, but a heated exchange instantly developed and lasted for several minutes, although it must be stressed that the seriousness of this debate, as repeated in several books, has most likely been somewhat exaggerated. Hackett demanded a sensible plan with definite objectives for his Brigade's advance on the following day, and after a further exchange the mood softened, and, on much better terms, the two men parted company. Hackett had obtained a plan that he was happy with; his Brigade was to seize several areas of high ground around the Dreijenseweg before a general advance towards Arnhem on what was believed to be the left flank of the 1st Parachute Brigade. Hackett was even happy, with a few reservations perhaps, for Brigadier Hicks to continue in command of the Division, though it was not until Major-General Urquhart returned on Tuesday morning that he had full confidence in the way in which the Battle was being fought.

The 4th Parachute Brigade's attack, on Tuesday 19th September, failed to break through the Sperrverband Spindler blocking line and, with very heavy casualties; they were compelled to fall back. After the Polish gliders had landed on LZ-L with the Third Lift, the Brigade began the slow process of transferring its vehicles and men to the other side of the railway line while German attacks continually harried them. Hackett put his HQ safely across, but he himself stayed on the northern side with a few of his officers as he noticed that the situation was confusing and could quickly escalate. He later remarked that it was a time when one needed great energy and violence to prevent this confusion.

Hackett has been criticized for not moving the Brigade into the Oosterbeek Perimeter during Tuesday night, when they could have been brought in safely, but instead rested them until the following morning, after which his men suffered heavily from the German troops following up their withdrawal. His diary notes that he wanted to move off, but was not at all adverse to the possibility of staying where he was until first light. He contacted Divisional HQ and they advised him to send reconnaissance parties forward during the night and bring in the remainder of the Brigade the following morning. Hackett did not see any advantage to this and instead waited until the morning before moving. The main reason for his reluctance was that large elements of the Brigade were still north of the railway line at this time and he did not wish to move away and risk losing them.

During the desperate fighting on the following day, Hackett showed great skill and courage in directing the movements of his men. German tanks began to surround the 156th Battalion, who had formed the Brigade's rearguard, and cut its men down in the woods with alarming rapidity; Lieutenant-Colonel Des Voeux and his Second-in-Command were amongst the dead. Lieutenant-Colonel Derek Heathcote-Armory (a friend of the Hackett's and a member of the GHQ Liaison Regiment, from whom he had taken two days leave and persuaded Hackett to take him on as a Liaison Officer, so that he could see something of war) was wounded and lying on a stretcher on the trailer of a jeep. Another jeep was parked next to this one, but its trailer, packed with mortar bombs, was on fire and could explode at any moment. Those in the area ducked to await the imminent explosion, but Brigadier Hackett risked his life to run over to the other jeep and drive his friend out of immediate danger. Heathcote-Armory recovered and was later to become Chancellor of the Exchequer in Howard Macmillan's Conservative Government.

Brigadier Hackett took temporary command of the 150 men that remained of the 156th Battalion and ordered them to mount a charge into an area of hollow ground in the woods. They arrived intact, but were pinned down here for the following eight hours. During this time the Battalion had to fight off repeated and violent German attacks with everything they had at their disposal. Every man was needed for the defense, and Brigadier Hackett did the job of any private soldier; he fired a rifle, lobbed grenades, and led the odd bayonet charge - it was a most unusual situation for a Brigade Commander to find himself in. Eventually Hackett ordered those men that remained to mount another bayonet charge to carry them into the British positions on the western side of the Oosterbeek Perimeter, a move that was totally successful.

The remnants of the 4th Parachute Brigade made their way to the eastern sector, where Hackett was given command of all of the units forming this front. Throughout the Battle, he was fearless in encouraging the spirits of the men under his command, and was constantly visiting their positions. On such occasions, he did not do the sensible thing and dive for cover in the nearest trench and so put himself out of danger, instead he stood upright and unfazed, talked calmly, and invited officers to stroll around with him, even in the midst of a heavy mortar barrage.

On Saturday 23rd September, a German officer traveled to the British lines in a half track under a Red Cross flag. He met Hackett, who had now been slightly wounded by an exploding mortar, and told him to withdraw his front 800 yards beyond the Main Dressing Station on the Utrechtseweg-Stationsweg junction, as the area was about to be heavily mortared. It was a puzzling proposal as the area had been shelled as heavily as the rest of the Oosterbeek pocket, however Hackett agreed as he saw this as an implied threat to the welfare of the wounded in the dressing station, but he insisted on only pulling back 100 yards as to go much further would have placed his front line behind Divisional Headquarters, which was clearly quite impossible. When the mortars began to fall, Hackett noticed that they had been carefully placed to the south of the dressing station.

At 08:00 on Sunday 24th September, Hackett fell victim to another mortar explosion at his headquarters and was badly wounded in the thigh. He fell to the ground and felt quite sick, but recovered after several minutes and began to make his way to the Divisional First Aid Post, though he stopped on the way to organize a stretcher party to bring in a man of the Reconnaissance Squadron, who had been acting as his runner and had broken his leg in the same mortar attack that had wounded him. Lieutenant-Colonel Iain Murray, commander of No.1 Wing The Glider Pilot Regiment, took over command of the eastern sector.

Sitting amongst the wounded in a cellar, Hackett was taken prisoner when several hundred wounded were evacuated from Oosterbeek under a truce on that same afternoon. He never let his true rank be known, but pretended that he was a Corporal to better his chances of escape. Moved to the St Elizabeth Hospital, he met up with a recovered Brigadier Lathbury who had also decided to escape, and so Hackett entrusted him with personal letters that he had written to his family and other officers in the Brigade, and also an extensive report that he had written on the battle, which included recommendations for bravery awards.

When the battle was over, lying wounded in a very sorry state, Hackett heard the sound of singing approaching. He was quite relieved at first as he thought that XXX Corps had at last arrived, but he soon realized that the singing was coming from captured men as they were being marched away. He said "After all they had endured, they held high their pride and they sang".

Brigadier Hackett's wounds turned out to be much more serious than was first thought. In addition to his thigh wound, a large piece of shrapnel, about two inches square, had penetrated his lower intestine. His life hung in the balance for several days, and a German doctor, who appeared to regard any wound to the stomach or head as one that could only be cured by euthanasia, declared that it would be a waste of time to operate. Realistically his chances of survival were 50%, but thanks to the work of the brilliant South African surgeon, Captain Lipmann Kessel, Hackett eventually recovered. As soon as he was fit to move, he escaped. With his bandages hidden under civilian clothes, members of the Dutch Resistance escorted him out of the hospital in broad daylight to a waiting car. He was taken to Ede, 10 miles to the west of Arnhem, where he was sheltered and nursed back to health by four very kind Dutch ladies; three of whom were elderly. Hackett made good his escape in February 1945, and eventually reached the Allied lines after a bicycle ride and canoeing around half of Holland; not an easy feat considering that he was still far from being in the very best of health.

Despite the optimistic assessment of Market-Garden by the likes of Montgomery and other higher echelon Allied staff, Hackett's view on the matter was "If you did not get all the bridges, it was not worth going at all."

For his actions at Arnhem, Hackett was awarded the Distinguished Service Order His citation reads:

At Arnhem from the 18th September until he was wounded this officer was continuously in close action with the enemy.

On the 19th September, his Brigade, which was engaged North of Arnhem railway met considerable enemy opposition. Despite innumerable difficulties he disengaged his Brigade and moved South of the railway to rejoin the remainder of the Division. During this disengagement and whilst moving through the woods to the West of Arnhem his Brigade became very heavily involved with strong enemy parties of infantry and tanks and a general melee ensued. Brigadier Hackett, by his personal example and leadership managed to extract a number of the Brigade and in spite of intense enemy fire brought them to within the Divisional Perimeter.

On the 21st September he took command of a sector of the perimeter which was made of many different units. Brigadier Hackett was tireless and quite oblivious to enemy fire when visiting his posts. Although almost continually assailed, the excellence of his arrangements was such that his sector of the perimeter was maintained. Until he was severely wounded on the 24th September, Brigadier Hackett showed inspiring leadership.

He was evacuated to hospital which was then in Germany hands. When he was about to be sent in to Germany, Brigadier Hackett, although he was not fit to move, managed to leave the hospital and took refuge with Dutch civilians. He remained in hiding until he was sufficiently recovered from his wounds and until arrangements could be made for him to rejoin our own troops South of the River Rhine.

The determination shown by this officer in the fighting and during the subsequent period in hiding was quite outstanding.

He was also Mentioned in Dispatches:

After being wounded during fighting at Oosterbeek on 24th September 1944, Brigadier Hackett was taken to St. Elizabeth Hospital, Arnhem, where an operation was performed the same evening. At this time the hospital was controlled by the Germans, and with a view to facilitating escape on his recovery, Brigadier Hackett got himself registered as a Major. Only three days after his operation he began collecting clothing and other escape aids. On 8th October 1944, although he was still very weak, Brigadier Hackett was evacuated by a member of the Dutch Underground to Ede. Whilst he was convalescing, Brigadier Hackett contributed to an Underground newspaper weekly notes on the military situation which he compiled from information received over the wireless; this activity ceased in December 44 when many Dutch workers were arrested. Several plans were made to get Brigadier Hackett through the lines, and he exercised daily in preparation for this event but it was not until the end of January 1945 that the journey was begun. He finally reached safety on 5th February 1945, after a strenuous journey by cycle and canoe.

During the post-war reorganization, when many officers of a temporary wartime rank were reduced to their official level, Hackett became a Lieutenant-Colonel and took up the position of GSO-1, Chief of Staff, to an armored division based in Italy. His experience with the Airborne Forces had not been a particularly happy one, and he was happy to be back with his native cavalry. He eventually became a General and held such prestigious postings as Commander-in-Chief of the British Army of the Rhine and Commander Northern Army Group in NATO. Awarded a knighthood, he resumed his old connections with the airborne as Honourary Colonel of the 10th (Volunteer) Battalion the Parachute Regiment, from 1965-73. From 1968-75 he was Principal of King's College, London, and held the post of President of the Classical Association, and the English Association of the United Kingdom. In 1977, he published his memoirs, I Was A Stranger, beginning with his being wounded at Arnhem and proceeding to detail the extraordinary events that culminated in his repatriation. He also penned the foreword to one of Geoffrey Powell's books, The Devil's Birthday, and also to Claude Smith's History of the Glider Pilot Regiment, Stuart Mawson's Arnhem Doctor and Kevin Shannon's One Night in June. Throughout the 1970's and 80's Hackett also wrote a number of best selling works of fiction, The Third World War, and The Third World War: The Untold Story. General Sir John Hackett died in September 1997.

Information from www.pegasusarchive.org

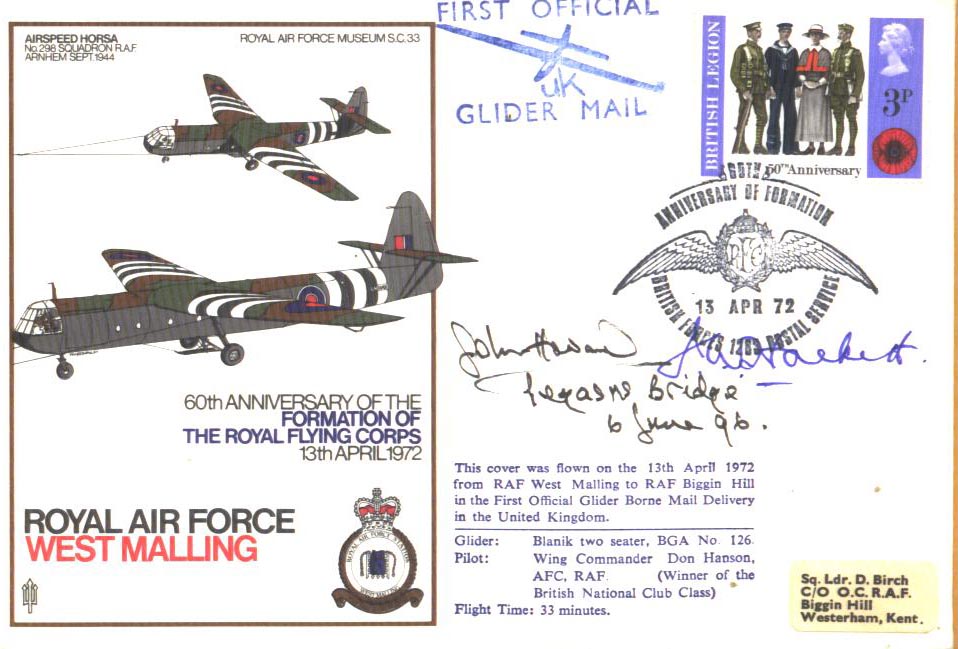

Signed 1972 commemorative cover featuring Horsa Gliders at Arnhem

Price: $0.00

Please contact us before ordering to confirm availability and shipping costs.

Buy now with your credit card

other ways to buy

|